I.

April 20th, 2020 — It’s day 35 of Philadelphia’s Covid-19 Stay-at-Home order. It’s also erev Yom-HaShoah (Holocaust Remembrance Day). Stuck at home, with past and future historical catastrophes on my mind, I find myself returning to a research project about my family history that I had put aside at the beginning of the pandemic.

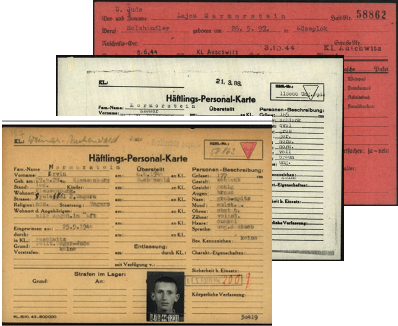

Among the online resources that have been posted for this socially-distant Yom HaShoah is a link to the Arolsen Archives, a collection of documents of Nazi persecution. A search for “Marmorstein” returns the Häftlings-Personal-Karte–the detailed documents that Nazis kept of concentration camp inmates–of a half dozen family members. I have childhood memories of some of these family members; others, of course, didn’t make it. These documents–combined with old family stories and emails and research trips to Romania and Hungary–fill in the details of a history that had long been murky and unformed in my mind. Along with the new information comes a new understanding of my father, available to me for the first time, barely a year after his death.

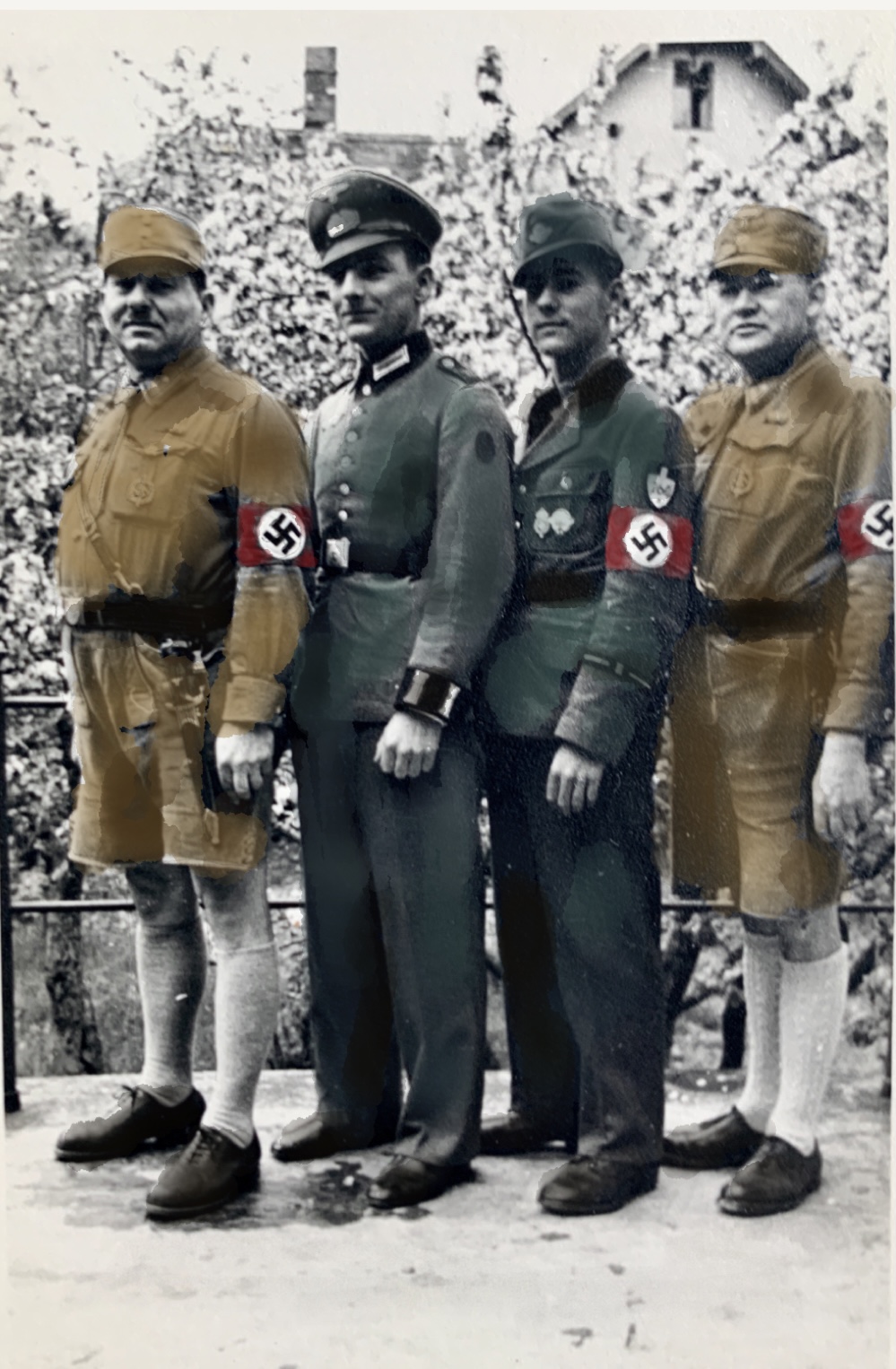

With such dramatic evidence of the ordeals of my father’s family, I turn to boxes of letters that I’d found in my parents’ attic to better understand my mother’s family. They’re full of hundreds of letters from my grandfather’s German family. My grandfather emigrated in 1928, and his Bavarian relatives were faithful correspondents for the rest of his life. These letters, as well as documents from the Bundesarchiv and travel to Germany, help me put together the story of my mother’s uncles, aunts and cousins. Almost all of them were active NSDAP members, many of whom fought and died in Nazi uniforms. Among them, one stands out to me: Karl was both a warm and generous host during my visits to Germany in the 1980s and 1990s, and also an SS officer, awarded the Iron Cross during the invasion of Poland. Of all the letters, the most heart-wrenching was sent in early 1946 and informed my grandfather about the deaths of his mother and uncle, of two nephews in Russia, and of his sister and almost her entire family in an Allied bombing of their Bavarian town. The date of the bombing? Exactly 75 years before that erev Yom HaShoah, 2020, the moment I began this investigation: April 20th, 1945.

II.

When I tell my family’s story, no one quite believes that my parents never figured all this out. It remained unspoken in my family, buried under several layers of family trauma and defensive forgetting. Both of my immigrant grandfathers died young–a defining loss for my young parents and a break with the countries and families that they had left behind. My parents honored their fathers in naming me: Jack, for my paternal grandfather; August, for my maternal grandfather. For a half century, I knew little about the men I’m named for.

I grew up in a rather traditional Jewish household: we kept Kosher (mostly) and I went to Hebrew school until my bar mitzvah. My mother converted to Judaism before she married my father. They lived in Israel together for six months before I was born, so they both fully participated in my Jewish upbringing. Yet looking back reveals something more complex in my development: the Volkswagens in the driveway, the German classes and trips to Germany in high school and college, and a lifelong interest in German (and German-speaking) Jews like Freud, Arendt, Kafka, and Benjamin suggest that I had created my own hybrid identity, mixing the legacies into something that never really existed: an American-born German Jewishness or a Jewish-American German-ness. Both carry difficult histories and complexities, yet my alchemy of identities may have offered a creative path out of the impasse of historical splits and unhealed wounds. The ultimate legacy of my grandfathers’ immigration is that I’ve been able to negotiate these identities in relative peace and security–an ocean away from the war that tore the previous generation apart.