From 1940, my grandfather in New Jersey didn’t hear from his family in Germany until more than ten months after the war ended. The letter he eventually received must have exceeded his worst fears. Even before reading it, he must have sensed the desperate times. It’s a single page, on paper so thin that it waves in the breath of its reader. The ribbon on the typewriter is still being used, even though it should have been replaced months or years ago. The letters are barely legible, and the margins are cramped. The text extends from the top to bottom, from the right edge to the left, suggesting that a single sheet of paper must have been a rare commodity.

The contents are heart-wrenching, at once desperately reaching out to a family member and also full of anger and pain from the war and its aftermath. It begins like so many letters to my grandfather begin, with barely hidden irritation that they haven’t heard from him. But the edge is sharper this time, as they had been through so much. It begins quickly, with one death after another. I even wonder if my grandfather might have skipped to the signature at the bottom, “Clär, with Irmgard, Irene and Walter.” Last he heard, his family in Memmingen numbered eleven: his mother, his two sisters and their two husbands, and his six nieces and nephews. This letter was from the four family members who remained.

First, Clär writes of the death from cancer of her husband, his brother-in-law, Georg. Then the deaths on the Eastern Front of Werner and Hermann in 1941 and 1943. “You can imagine how that was,” she wrote her brother, who she must have known couldn’t possibly imagine. She continued, “But life and war went on and we just hoped that these horrific victims wouldn’t have died in vain. But slowly you realized what was coming.”

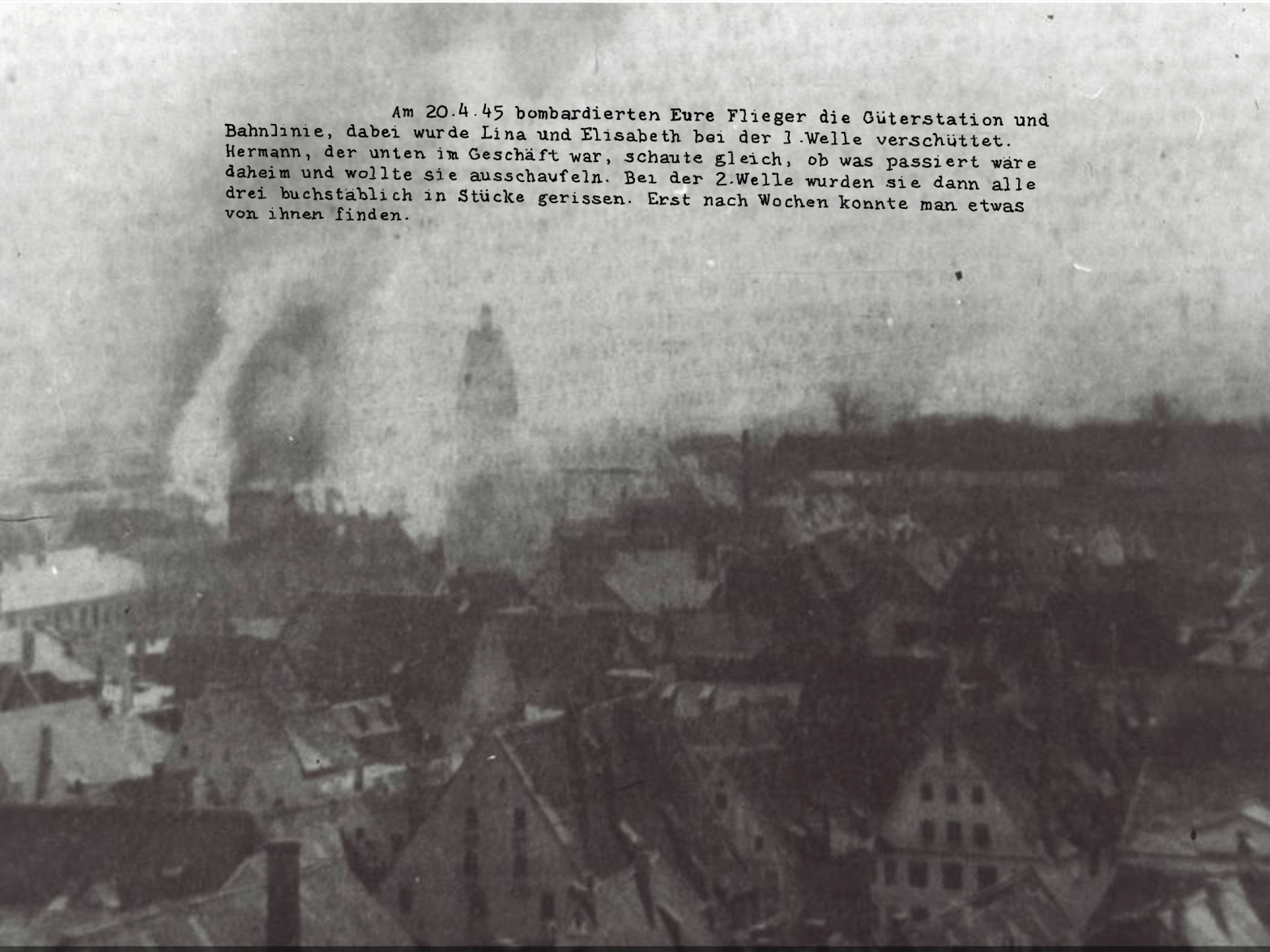

1945 began with the death of his mother, following a fall. All this was old news, though, by the time that Clär wrote this letter. It’s related in quick, short sentences, more a list or a timeline than a story. But then a detailed description of a horrific Allied bombing opens like a wound in the middle of the page, angry words overflowing the terse economy of the rest of the letter:

Could we have imagined that more deaths would follow? We had had a few attacks on Memmingen and we always got through well. On April 20, 1945, your planes bombed the freight station and railway line, and Lina and Elisabeth were buried in the 1st wave. Hermann, who was down in the shop, immediately checked to see what had happened at home and wanted to dig them out. In the 2nd wave, all three of them were literally torn to pieces. It was weeks before anything of them was found.

Hätten wir uns gedacht, dass noch mehr Todesfälle folgen? Wire hatten ein paar Angriffe auf Memmingen und waren stets gut durchgekommen. Am 20.4.45 bombardierten Euro Flieger die Güterstation und Bahnlinie, dabie wurde Lina and Elisabeth bei der 1.Welle verschüttet. Harmann, der unten im Geschaft war, shaute gleich, ob was passiert wäre daheim und wollte sie ausschaufeln. Bei der 2.Welle wurden sie dann all drei buchstäblich in Stücke gerissen. Erst nach Wochen konnte man etwas von ihnen finden.

My grandfather had opened that envelope and learned that his mother, his sister, an uncle, two nephews and a niece were dead. Your airmen, Clara wrote. My grandfather had been raised in the town that had just been bombed; he had just been informed that his mother had died, his nephews killed in combat; he was reading the letter in the occupiers’ country, from his German sister, with news of his German family’s deaths, yet it was his aviators who had dropped the bombs that killed his family.

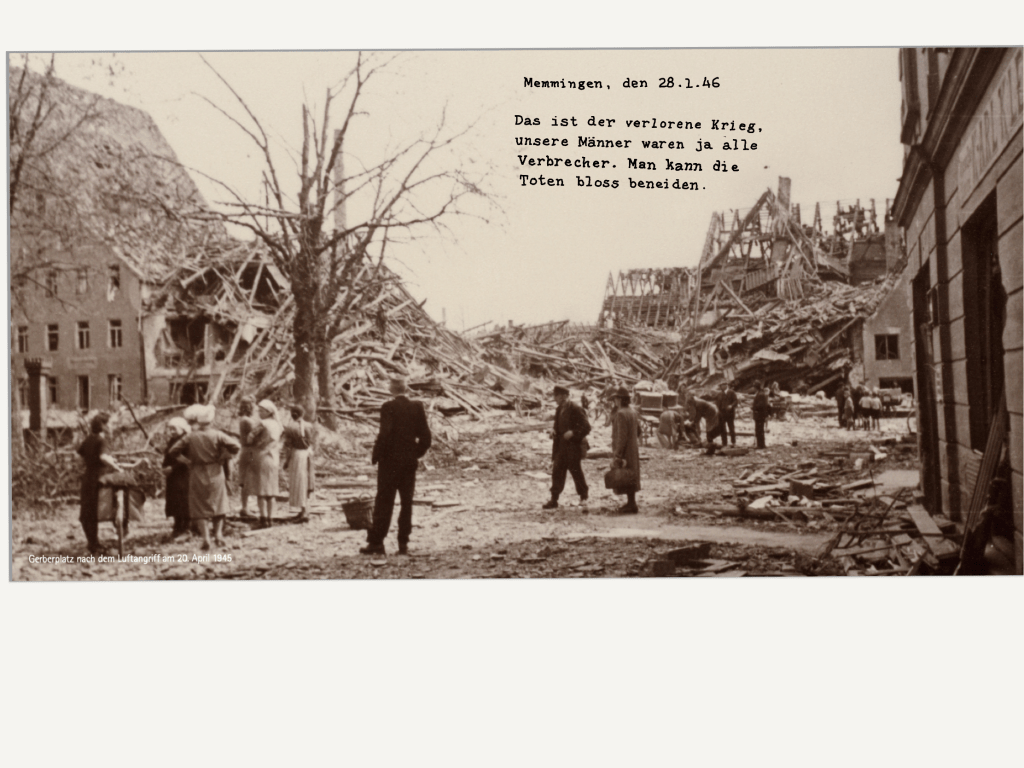

Lina, the one who had written of the “maleficent war,” had lost her two sons in combat before losing her own life, along with her daughter and husband, in an Allied bombing. Clär’s words scream in agony from the cramped type of the page: “This is the lost war. All our men are regarded as criminals. One can only envy the dead.” It’s signed by Clär, her children, Irmgard and Walter, and their cousin, Irene, the sole survivor of her family of six.

**

The bombing raid on Memmingen that day was aimed at a railway depot where troops and munitions were transported to where they were needed. It came just three weeks before Germany’s surrender, at a time when Allied bombers were conducting raids against ever weaker German air defenses. It was the day that Soviet shells began to land in Berlin; also the day that Göring and Himmler fled Hitler’s bunker, abandoning Hitler on his 56th birthday. Allied troops were closing in on Berlin from all sides. The day’s headline in The Cleveland Press reads “Reds Battle to Berlin’s Gates.” Six days later, a letter signed by the Memmingen mayor announced Memmingen’s surrender.

In 1979, a local historian would record Irene’s oral account of the bombing that killed her family. Even thirty four years later, her memory of the day is seared with pain:

April 20, 1945 One month after leaving school, I was assigned to work as an intelligence worker in the Air Force at Memmingen Air Base. In the summer of 1944 I spent a few weeks at the Mengen / Württemberg air base as a vacation replacement. As a result, I escaped the attack on the Memmingen air base on July 18, 1944. My parents were always afraid for me because my two brothers had died in Russia in 1941 and 1943. That is why my father tried to get my exemption from military service at a personal presentation in the Luftgau in Munich. It was in vain. The only success of his endeavor was my transfer back to Memmingen Air Base. From October 1944 onwards, I rode my bike every day to work at Schloss Eisenburg, a branch of the air base’s intelligence department. When the air raid on the city of Memmingen by American bombers took place on April 20, 1945, I was on duty in Eisenburg. The teleprinter reported that strong formations were approaching Memmingen. Somehow I was already afraid for my parents and my little sister in our house on Steinbogenstrasse. When the first bombs fell, the cellar doors even in Eisenburg Castle, 5 km away, rattled so hard that we thought the air base was being bombed. After the first wave we immediately ran upstairs and saw with horror that smoke and smoke were rising in the city, especially near the Frauenkirche. My fear grew minute by minute. My colleagues prevented me from riding my bike into town immediately. And then on the next wave of attacks we saw the bombs drop straight from the planes onto the city. When the last bomber formation turned off, I could no longer obey any regulations. I rode from Eisenburg to Memmingen at a pace never again in my entire life. It looked terrible in Kalchstrasse and Salzstrasse. Everywhere there were stones, glass, roof tiles and bomb fragments on the streets. Things got worse at Gerberplatz, the street was covered with rubble. Sometimes I had to carry the bike to get anywhere.

In the Hirschgasse and at the Frauenkirche, the air pressure from the bombs covered all the roofs and splintered doors and windows. It smelled of fire and mold. The growing fear drove me forward. At the Frauenkirche everything looked very different than before. The large parsonage we had often played in as children was no longer there. Then I came to Steinbogenstrasse, I screamed in horror! There was a nasty bomb crater where my parents’ house had stood, and in our garden with its many trees, more bombs had destroyed everything and tore it apart. My only thought was: where are my parents and my little sister? I kept shouting it, but nobody answered me. I just couldn’t believe it, it was incomprehensible. Now I was all alone. It wasn’t until a few days later, when many helpers searched the rest of the house for any buried people, that I became fully aware: I was the only one left of our family of six. Irene Sprick, b. Scheffel, housewife Hirschgasse

There’s no account of Irene’s brothers’ deaths of Hermann and Werner on the Eastern Front, but it’s possible to find records of them on the Internet. My searches of their regiments and roles on the internet offer some reassurance that they weren’t involved in the systematic extermination of Jews and certain civilian populations that followed the Nazi march eastward, but there’s no way to be certain. Given what we know about the warfare in the East, though, it’s almost certain that their last years were spent in abject conditions, living in a constant state of fear and suffering. Obergefreiter (Corporal) Hermann Scheffel (Bibi) was the first to be killed, on October 7th, 1941, in Michailowka, on the river Bogataja. And Unteroffizier (Sargeant) Werner Scheffel was killed on November 27th, 1943, in Schäferei, ten kilometers southeast from Bol Lepaticha. Both died in what is now the Ukraine, in areas of fierce fighting, two years apart, hardly differentiable from the more than two million other German casualties of the war in the East, and unremembered only a generation later, when Martin knew of Irene’s two daughters but knew nothing of her two sons.