By the time the traumatic memories get to the second and third generations, they’re literally impossible to remember and paradoxically impossible to forget. Burdens too great for parents to bear are unconsciously passed to the children, who are haunted by the memories that were never theirs. This has been what generations of Boss’s and Marmorstein’s have carried since the 1940s. In the early years, the trauma metastasized in my mother’s and my father’s families: their fathers died prematurely, leaving my parents to carry–and bury–the burden through their lifetime, marrying across enemy lines, and spending the rest of their lives not quite realizing what they’d done. Now, they’re gone, and I’m sifting through the evidence, to see what’s unrememberable and what’s unforgettable, who’s haunted, and what my generation can do that previous generations have been unable to.

I have to remember that, having learned all that I have, I still haven’t learned the truth. I mustn’t fool myself: I can’t uncover that which no longer exists. Very little of this lurked inside my parents’ psyches. The dark masses they carried–the tumor inside my mother (irradiated once to make it appear, irradiated a second time to make it disappear) and the thing under my father’s skin (casually tossed in the trash by the otherwise helpless doctor) are not onions to be peels, nuts to be cracked, eggs to hatch, or embryos to develop. They’re impenetrable, literally unrememberable, inaccessible, unknowable. But for all that, what I have learned is substantial. I’ve biopsied the history and this is what I’ve found:

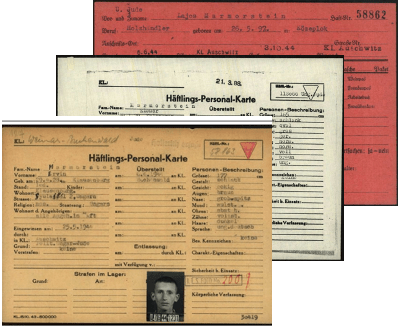

My mother was born on October 16th, 1941, the daughter of immigrants, in Trenton, New Jersey. Nine days earlier, her cousin was killed in the Ukraine. When she was one, an uncle died of cancer. Six weeks after her second birthday, another of her cousins was killed in the Ukraine. In January, 1945, a few months after my mother turned three, her grandmother died after a short illness. Later that year, on the 20th of April, her aunt and uncle and another cousin were killed in a bomb blast. The war in Europe ended just a few weeks later. In a period of seven years, my mother’s father–my grandfather–had lost both his parents, his sister, two brothers-in-law, two nephews and a niece. Of the three generations of his family in Germany, there were only four survivors.

My mother remembers none of this. Whatever level of stress and anxiety permeated her family during those years, it was her normal. And even if growing older meant a dawning awareness of the circumstances of the first years of her life, any look back at her early life was darkened by the enormous shadow cast by her father’s sudden death when she was a teenager.

My father was born on July 24th, 1941, the son of immigrants, in Cleveland, Ohio, just a year after his parents had lost their three-year-old daughter, a sister he would never meet. A month after he was born, his grandmother died. His grandfather died when he was two. An uncle was killed in Germany a few months before he turned four. When he turned five, two aunts and two uncles and ten more cousins remained missing in Europe. Ultimately, six would turn out to have survived; eight others didn’t. When he was seven, three cousins arrived in Cleveland from Europe, where they had survived the horrors of the Holocaust, and an uncle was murdered in Florida. By then, there were no Marmorstein’s remaining on the continent where they had been for centuries.

My father’s memory of these years was, like my mother’s, non-existent. And like my mother, any capacity to reflect on his childhood experience was eclipsed by the sudden death of his father, in 1952. That was followed by a serious auto accident that nearly killed him. An uncle shot himself two years later.

Nearly half of my parents’ families had perished during the first five years of their lives, yet they knew next to nothing about it. The last letters to come from Europe in 1939 and 1940 bore stamps of Nazi censors. When the letters resumed in 1946, they bore the stamps of US or Soviet censors, or came from the Red Cross and the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee’s Immigration Service. The Americans only learned the complete fate of their European families after the fact. My parents were too young to have any memory of the news arriving, even as it’s impossible to imagine how it affected their fathers.

More of their families perished between 1940-1945 than in the rest of the 20th century combined, but my parents would describe their early years as normal. They grew up more worried about polio than about warfare; when they got older, they had vivid memories of the Cuban Missile Crisis and the draft, not of death camps and bomb shelters. There were few funerals to attend nor graves to visit. No yahrzeits to observe; in most cases, the circumstances of death would never be known.

All this had happened, yet my parents didn’t know a thing about it. It wasn’t like they came to some belated awareness of it all. They never tried to reconstruct the story and contemplated the losses that must have haunted their early years. In fact, no one would tally the death toll until I eventually put together all the pieces in the spring of 2020. This has been the story of putting together those pieces.

Immigrant families use the language of the Old Country to talk about such things, precisely so the children can’t understand. It was wartime and they weren’t alone in worrying about those endangered in Europe. Millions of Americans had sons fighting in the war, but only my mother’s father had to look over his shoulder, aware that, as a German immigrant, he could be surveilled by the government or harassed by people around him. My father’s father read the newspaper obsessively, holding on to his collection of newspapers tracking Hitler’s defeat for the rest of his life. To whatever extent their parents were worried sick for their families in their native lands, my parents would only have felt it at the level of something passed unconsciously, in mood or vibration or some other quality that my parents could only have known as the norm, not the exception.

In her groundbreaking research on Germans who were children during the war, Sabine Bode came to a counterintuitive conclusion. One might assume that the long term impact of the war would be greater among children who were old enough to have conscious memories of that time, those who were five or ten years old and remembered bombs and violence and death. But she found the opposite: those who were too young to have any conscious memories of the war at all showed greater signs of being affected by trauma through their lifespans. She writes:

The younger the children were when the catastrophe hit, the more serious are the long-term effects. Interestingly, the largest impairments are visible among those who were born in the 1940s and can hardly remember events of the war, if at all. (https://www.sabine-bode-koeln.de/war-children/the-forgotten-generation/)

Bode estimates that “One could say that a third of all of those who spent their youth or childhood in war – e.g. children born between 1928 and 1945 – are still struggling with the long-term effects today.”

Growing up, my parents said so little about all this that I simply assumed that their childhood was as boring as mine. They barely spoke of their fathers, and didn’t mention their families in Europe, except when we visited my mother’s relatives there in the 1980s. My parents honored their fathers by naming me after them–Jack, for my paternal grandfather; August, for my maternal grandfather–but I don’t know if I saw a photograph of either man until I was in my twenties. In fact, for a half century, I knew next to nothing about the men I’m named for. This has been the story about how that changed, and about how what I learned changed the way I think of how we all become who we are.