Left with only Martin’s words and my father’s email recollections, I wondered if there was more to learn about Karl. When I visited Martin again in 2016, I asked more questions and he repeated his belief that Karl had been in the SS. He also spoke vaguely about Karl’s retrograde misogyny and nationalism, mentioning avuncular advice he had received about how to treat women; chauvinistic ideas about feminine emotions and irrationality; and a reactionary nationalism that Martin didn’t think had changed much since the 1930s. It was an ugly portrait, and not at all the Karl my mother and I had such fond memories of. But what could I know? I had known him for a week–my mother, for a few weeks more–but Martin had spent his lifetime with the man. It was his family and cultural context, not mine.

I had no reason to distrust Martin and that not only meant reassessing Karl, but reassessing myself: how would I respond to a right-wing, nationalist, misogynist veteran of Hitler’s SS? For many, it would be a hypothetical question. For me, the answer was staring me in the face: I quite liked him. He seemed pretty wonderful, and treated me and my family with nothing but kindness and warmth. Did I feel different about him now that I knew more about parts of him that lurked beneath the surface?

I still didn’t feel like I knew enough. I had heresy, embedded in family dynamics, and at a remove from my own experience. But perhaps I didn’t just have to rely on my father’s or Martin’s recollections about what Karl did during the Nazi era. If he had been in the SS or a party member, there would likely be a record of it. So with little in the way of know-how and zero experience, I began the long process of learning how to research in Germany’s archives: the Memmingen city archive; the Bavarian state archive; the archives of German military service in [find where??], and the German Federal archive in Berlin. Navigating the archives’ bureaucracies wasn’t easy for me, but after a while, I got the hang of it. I found the person to email, the form to fill out, or the online records to search.

Mostly, there were dead ends: no record of any Karl Lierheimer in Memmingen archive; the location of Allied de-Nazification records depended on where he had been when the war ended, which I didn’t know; no response from the Bavarian state archive. In most cases, I didn’t even know what I was asking for and found nothing. But after weeks of searching, I finally found an online record of a file in Karl’s name.

After filling out more forms and agreeing to pay the archivists for their research, I was told they had the file, but to see it, I either had to come to the reading room–impossible anyway because of Covid–or contract with a separate company to make scans, burn a CD-ROM, and mail it to me. It was a process that would end up taking six months. I had no choice but to opt for the latter and wait. In the meantime, I held onto my screenshot of the record of the file bearing his name, sometimes feeling like this would be all I would ever know.

While I waited, I learned I wasn’t the only one waiting. Reading news articles from Germany revealed that I’m far from alone in my research into lost family stories, particularly as the generation postwar children were aging and trying to make sense of the gaps in their own family histories. In recent years, aging family members have flocked to the various branches of archives–the Deutsche Dienstelle for military service and the Bundesarchiv for political records. These archives all draw people hoping to learn more about their family history, and perhaps to fill in gaps about their own parents and in their own childhood memories. It’s a moment when the war generation itself is almost gone and the Kriegskinder are growing old. When Burkhard Bilger went to research his family for the New Yorker, an archivist said, “We’ve just been flooded with inquiries. War veterans and their wives have priority—they’re often dying. But even their children aren’t so young anymore. After that, who’s to decide who comes first?” (September 12, 2016 “Where Germans Make Peace with Their Dead”)

Months passed while I waited for the CD-ROM. My faith in the efficient German bureaucracy faded, replaced by a sense that my request was lost somewhere I couldn’t go, in a language I struggled to understand, with people who probably had little interest in an American’s curiosity about his mother’s cousin. Finally, I was notified that they had sent the CD-ROM and emailed the tracking, but actually tracking it proved futile.

It had disappeared without a trace, somewhere between the Bundespost and the US Postal Service. It was the fall of 2020, a time of Covid and of the US presidential election. The performance of the US Postal Service was the subject of much controversy: strained by the quantity of mail order deliveries during lockdown, facing the challenges of managing an essential workforce during a pandemic, and under scrutiny for the key role mail-in ballots would play in the upcoming election, no one was very happy with the postal service. After three months, I had given up on receiving the CD-ROM.

After a few more months, during one of my random attempts to enter the tracking number into the post office website, it appeared. It had cleared the blank space between the Bundespost and the USPS and was on its way to Philadelphia. It still took a few more weeks, but it finally arrived, and I dug out an old CD-ROM player from the drawer of obsolete electronics and opened the files.

I had no idea what I would find. The archivist who had collected the material hadn’t gotten my hopes up. He suggested that the findings were nothing special, but I couldn’t gauge his threshold for special. The CD-ROM contained one folder, consisting of high resolution scans of sixteen pages, several of which were duplicates, or the blank backs of forms. I started with the two copies of his service record, as they promised a comprehensive story of his war.

Each of the two copies has identical entries, listing his battalion and unit, and tracing his deployments, from the force occupying Poland from January to May 1940 to the coast of Belgium from May to August 1940. Then there’s a gap until May, 1941, when he joined the 9th Army in Russia. On September 13th, 1941, he was awarded the Iron Cross, second-class. On November 11th, 1941, he was wounded by shrapnel from a grenade in the right knee and foot and evacuated from the front. On January 6th, 1942, he was awarded the Wound Badge (the German equivalent of the Purple Heart), and as far as these records go, that’s the end of his war.

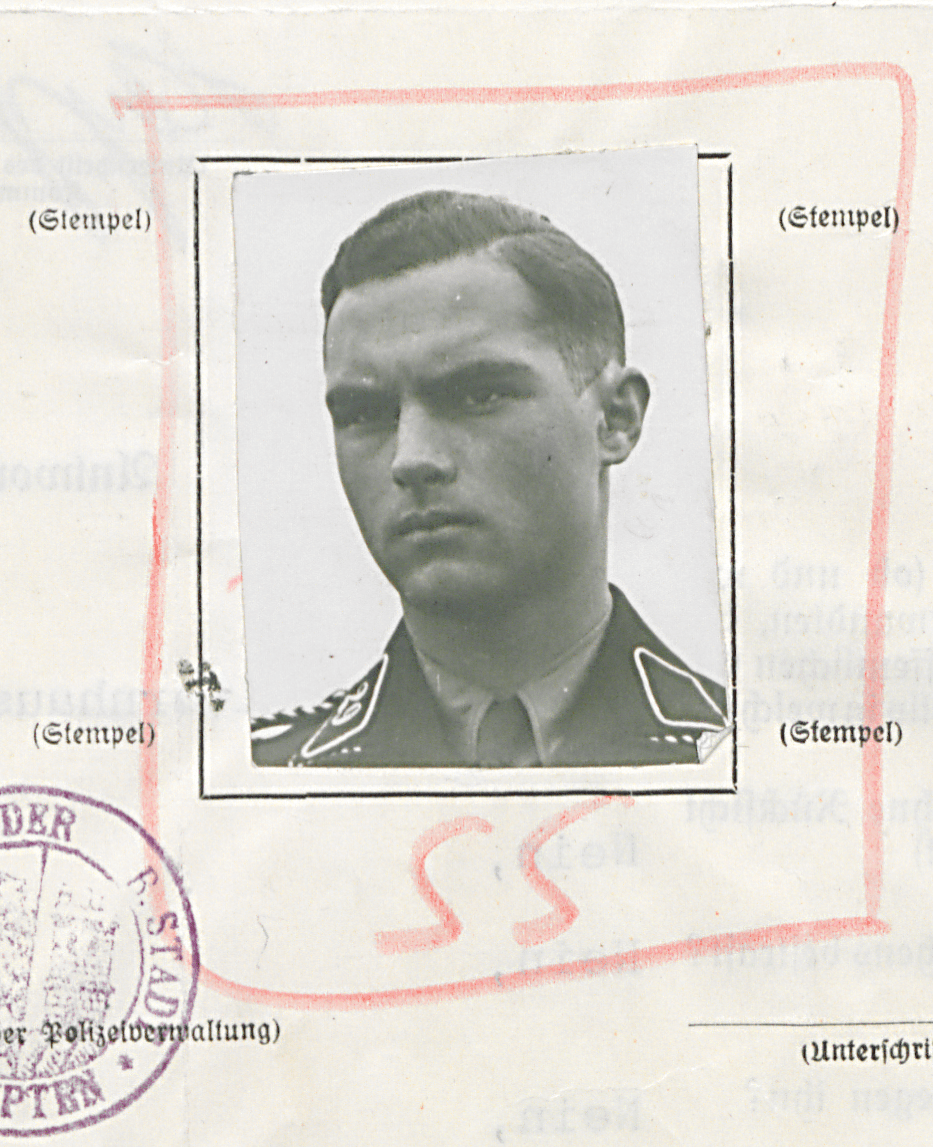

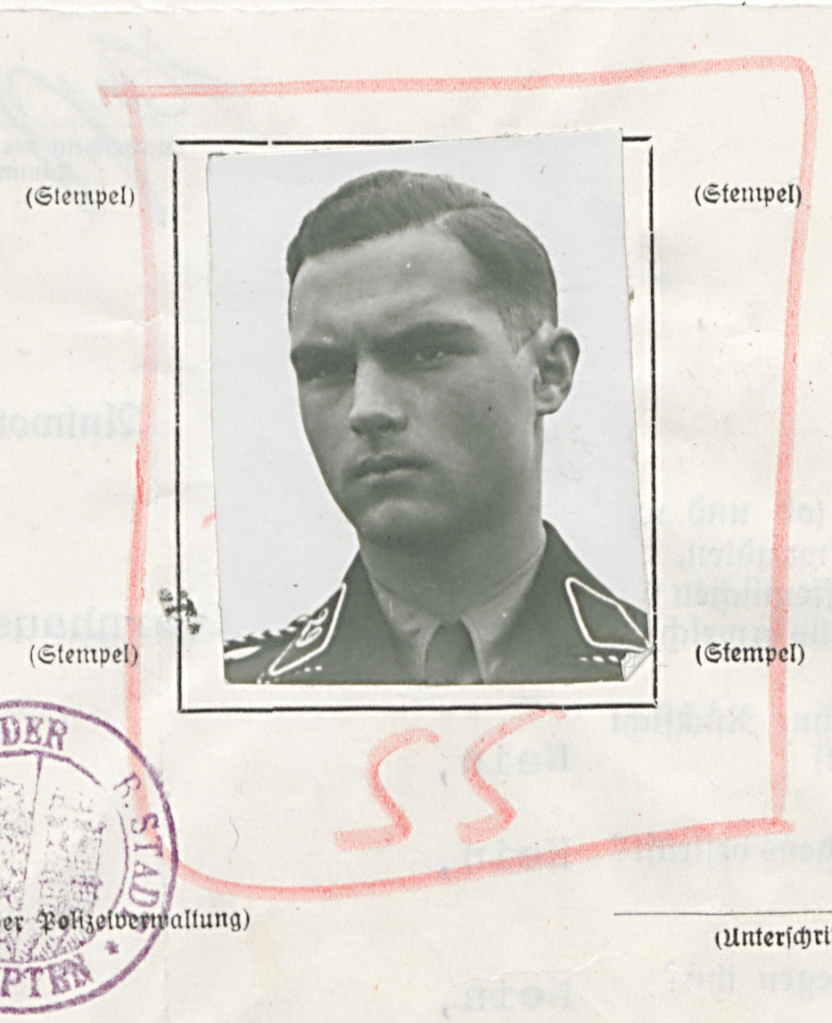

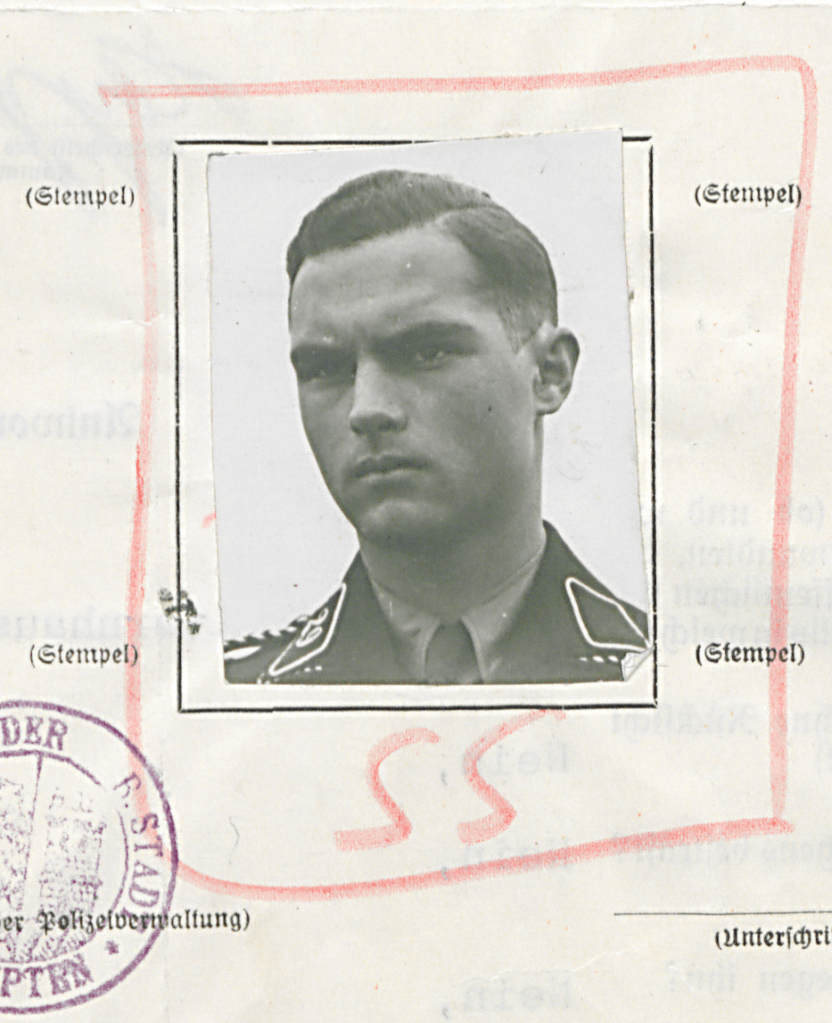

The interesting thing about these two copies of his military record is this: while they are identical in content, each copy has a different photo attached to the form. Both are headshots or Karl in his SS uniform, but in one, he sports an awkward smile and nervous eyes, like he’s uncertain about how he should look. In the other, he’s scowling, his brow furrowed and chin set, in a way befitting a true believer in the thousand year Reich. Seeing them side-by-side, I can’t help but imagine the photo shoot: Should I smile? Should I scowl? Charming Karl? Menacing Karl? Oh, just take both. We’ll decide which to use later. Today, they reveal an uncanny capacity for shapeshifting, both in Karl’s self-presentation and also in the viewer’s own assessment of the man in the photo. In these pictures, both the prosecution and the defense can find support for their cases.

In addition to the service records, there’s a form with a handwritten biography, beginning with his birth in 1914 and mentioning his mother and father and listing his schools in the order he attended them. In the biography, he lists joining the Hitler Youth in July 1932 and the SS in 1933. On a 1934 document, there’s a list of biographical questions and possible political crimes, printed in ornate gothic script. Here, Karl answered questions about marital status (“single”), reputation (“very good”), and abnormal sexual tendencies or psychological defects (“no”). At the bottom, there’s a photo of young Karl, with furrowed brow and dark scowl. At some point, someone pencilled a red square around the photo, with “SS” written in big red letters underneath it.

The Nazi mania for interrogating the ideological purity of its soldiers continued in 1939, when Karl filled out his Erklärung über politische Vergangenheit und Einstellung, or “Declaration of political past and attitudes.” On it, he answers that he’s never taken part in any activities of the communist party, pacifist movements, or any of seven other organizations contrary to Nazi ideology. He reports joining the NSDAP in April, 1937, and he reiterates his belonging to the Hitler Youth and the SS. On another form indicating his presence or absence at the local command in Kempten, he answers the question of whether he belongs to the SA, SS, NSKK, or Hitler Youth by indicating that he’s an “SS Mann,” a private in the SS.

That’s about all there is to it. There’s ample information to confirm my cousin Martin’s assertion that he was in the SS. And there’s confirmation that what he told my father about his activity during the early parts of the war is roughly true: he indeed served the occupying forces in three countries and saw combat in at least two. There’s no record of how he earned his Iron Cross. Missing is any information to confirm or deny the family story that he spent his time after 1941 behind a desk, a low level bureaucrat, but he must have been doing something after being wounded and until the end of the war in 1945.

There is, though, one more photo–that makes four photos in a file with only about seven substantive pages of content. This last one is simply attached to a blank piece of paper. It’s a portrait of Karl, in civilian clothes. By any measure, he’s strikingly handsome. The lighting is dramatic, his hair and wardrobe are immaculate, and he looks more like the headshot of an aspiring Hollywood star than either a student or a soldier. There’s no indication of why such a photo would be in his military file. This last photo reminds me of the septuagenarian charmer who my mother and I knew, but it doesn’t exonerate him of being the retrograde nationalist of Martin’s childhood memories.

* * *

I recently learned one more story about Karl during the Nazi years. It’s a dramatic one and speaks to the turmoil and complexity of the 1930s in Germany. All political and moral judgments of the era occurred in an environment of instability and upheaval. This story relates the actions of twenty-year-old Karl and others his age as they tried to navigate the chaos of the day, but first, a little background.

The region where my whole family was from had always been conservative. The population had been supportive of Hitler and his Nazi party from the beginning. Hitler based his early efforts out of Munich, drawing largely on the support of World War I veterans. These men not only endured the trench warfare, but also suffered from the shame of surrender, humiliation of the Treaty of Versailles and the economic and political turmoil that followed. Their combination of resentment, nationalism, and conservatism made them easy recruits for Hitler’s movement and they joined the Sturmabteilung, the SA, in great numbers. These were the stormtroopers, the brownshirts, who were Hitler’s enforcers in the early years of the Nazi Party. The photos I found show both my grandfather’s brothers-in-law in SA uniforms.

The SA grew to be enormous—at its height, it boasted over four million members. People feared its mob violence and vigilante justice and it wielded significant political influence. One peculiar—and effective—aspect of the way Hitler ruled was his aversion to any one faction within his political organization gaining too much power. To prevent this, he frequently pitted factions against each other, both to prevent any one from becoming too strong and to force them compete for his favor. Hitler himself would shift his favorites often, keeping his loyal followers off-balance and eager for any chance to prove their allegiance, with a keen eye for the missteps of their rivals.

During Hitler’s early days as Chancellor and Fuhrer, the rivalry between his faithful SA and the newer Schutzstaffel (the SS) was growing. The Munich-based SA had followed him to Berlin, but Hitler’s new national presence opened the door for the growing prominence of the SS. The conflict reached its climax at the end of June, 1934, on what has later been called the Night of the Long Knives. Hitler ordered a purge of the SA, authorizing members of the SS to arrest and imprison its leaders. Several were killed and overnight, the SA was driven from its position of influence. The purge changed the tenor of Nazi paramilitary leadership. Gone was the SA’s populist mob—embittered veterans, resentful nationalists, and people from the countryside who thought of themselves as fighting for traditional ways. They were replaced by the more sophisticated SS, fitting Hitler’s transition from Bavarian rabble rouser to the country’s new absolute leader.

My grandfather’s brothers-in-law were of the conservative countryfolk mold. Their generation was traumatized by the war, impoverished by the decade of economic upheaval that followed, and enraged by the communist and socialist movements that gained prominence in other parts of Germany. Memmingen and nearby Kempten, where Karl was from, were SA strongholds. In fact, there was to be a mass meeting of the SA in Kempten soon after the Night of the Long Knives. Nazi party authorities, nervous that such a meeting could take up arms to fight back against the crackdown on its leaders, announced that the meeting was cancelled and forbade SA members from gathering.

It’s here that the story Karl’s grandson told me begins. At this time, Karl was a cadet officer in the 19th Infantry Regiment in Kempten. He and his fellow cadets were local boys serving under Eduard Dietl, who would go on to become a celebrated Nazi military leader. The Nazi party ordered that Karl’s regiment take up positions on the roads leading to the SA meeting to prevent anyone from attending. According to Karl, they dug trenches and loaded machine guns with ammunition, knowing that the order could come to open fire on approaching SA members. But to the young soldiers, those weren’t just members of an outlawed political faction, they were their fathers and their uncles, their family friends and men they had grown up with. Karl proudly told how he and his fellow cadets decided among themselves that they would refuse any order to fire, even if it meant court martial.

It never came to that. The SA threat never materialized and the cadets were ordered to stand down. Karl told this as a story of the moral character of the Army in which he served. It also paints an evocative image: young men choosing to refuse a direct order of an authoritarian state; sons showing loyalty to fathers; and humanity in the face of cruel political rivalries. But the evil of Nazism has never been the same as the evil of every decision by everyone involved. At best, Nazism was a cancer infecting the decisions of even every day Germans. Nothing can be entirely separated from the broad national consent—and widespread enthusiastic support—for a regime built on fanatical hatred. At worst, looking after one’s own, whether by the SA or the SS, or by the boys of Kempten or their fathers, was a symptom of the disease itself. Perhaps this only illustrates the way anyone in a disordered society can turn on anyone else to save their skin.

Nothing I saw in Karl makes me think that he was a bad man. But as soon as I think something like this, I wonder what I really even mean? Like many Nazis, he loved his family, treated those around him well, and believed he was acting in the best interest of those he cared about. Similarly, I have no reason to doubt Martin’s stories that he remained a conservative nationalist, with retrograde attitudes about gender and likely race as well. Politically, I’m sure I would view him as an enemy, someone whose views do harm in the world. In an American context, were he a rabid Trump supporter, a misogynist or racist, it might be easier for me to hate him. As to what he did during the war–the mundane, the heinous, the heroic, the cruel–anything is possible and nothing can be known for sure. But even knowing all this, I still remember him as a funny and warm-hearted man, and a caring and loving family member. Maybe that’s just a lesson about life: everyone is complicated. In a functioning society, people’s complexity can be channeled in ways that minimize its danger. In a society descended into murderous madness, on the other hand, people’s complexity can have the very darkest consequences.

Karl, far left, and me, far right. First cousins Irmgard and my mother in between