- “A Jewish Forest-Owner”

More than three years passed from the time when I heard about Középlak in Tsfat in 2016 to when I set foot there in the end of 2019. Now that I had heard about “Of Marmorstein,” I was determined to return as soon as possible. It was land that my family had owned in my father’s lifetime, and I wanted to get to the bottom of the mystery. I got in touch with researchers who could help scour Romanian and Hungarian archives and I corresponded with academics who studied that period. I began studying Hungarian, and I even took on consulting work that would have me take me to Europe a lot. I would certainly be back in a matter of months. Nothing could keep me away.

Then, of course, everything changed. I shouldn’t have been surprised. Right before I’d traveled to Romania, I’d spent two weeks in Beijing, and staying in touch with Chinese friends and colleagues into January and February gave me a glimpse of the future. I began noticing their WeChat posts about how to entertain bored kids at home and how to cook with shortages of certain staples it slowly dawned on me that they weren’t leaving their homes; their kids weren’t going to school; their offices were closed; Beijing’s six, twelve-lane ring roads were abandoned. Life had come to a screeching halt for a hundred million people in the world’s most populous nation and no one here seemed to notice.

In a flash, it seemed utterly clear to me: WeChat was showing me the future. It wasn’t that I knew every detail of the future; in fact, it was the uncertainty that unnerved me. How could tens of millions of people stay home in the world’s most dynamic economy and the effects not ripple around the world? How did two of the world’s megalopolises come to a screeching halt and we didn’t even notice. I didn’t know how, but it seemed blindingly obvious that everything was about to change. Soon, their reality was ours: lockdowns, shortages, bored kids, canceled plans, and vacant roads and offices. And still, I remained optimistic. Maybe it would be August before I got back to Romania. They were sure to have a vaccine by then, right?

In the meantime, I would have to learn what I could from home. The internet is nothing if not a genealogist’s dream, but I didn’t know where to start. I had never paid much attention to family history, and on the rare occasion when I had tried to figure it out, I was overwhelmed. My grandfather had six older siblings and five younger ones. My father had dozens of cousins. Moreover, my grandfather died in 1952, nearly two decades before my birth, so my direct link to the Középlak and “Of Marmorstein” was but a memory of my father’s boyhood. The last of his generation died in the early 1990s. Even the next generation was mostly gone. The loss of my own father remained fresh. He had died a year before Covid, in 2019, on my fiftieth birthday. If anyone had left anything behind, I wasn’t aware of it.

The only family member with an interest in its history—the one who had preceded me at the Museum in Tsfat, the one whose signature I had seen in the guestbook there—had taken her own life less than a year ago. If only I’d started this project earlier. Once again, it all just seemed too late.

When I extended my sympathies to the family historian’s son, we exchanged a few emails and he shared an online folder of materials from his mother’s archive. I knew this was a treasure trove, but I had no idea what I was looking at. What if the key to these images had died with her. What I saw was a confusing jumble of documents with unfamiliar names and photos of unrecognizable faces. I stared at the files and felt even farther from ever understanding. Some names rang a bell from my childhood, but everyone I might ask was gone. Some photos had captions, but they raised more questions than they answered. I doubted I could ever make any sense of it all.

* * *

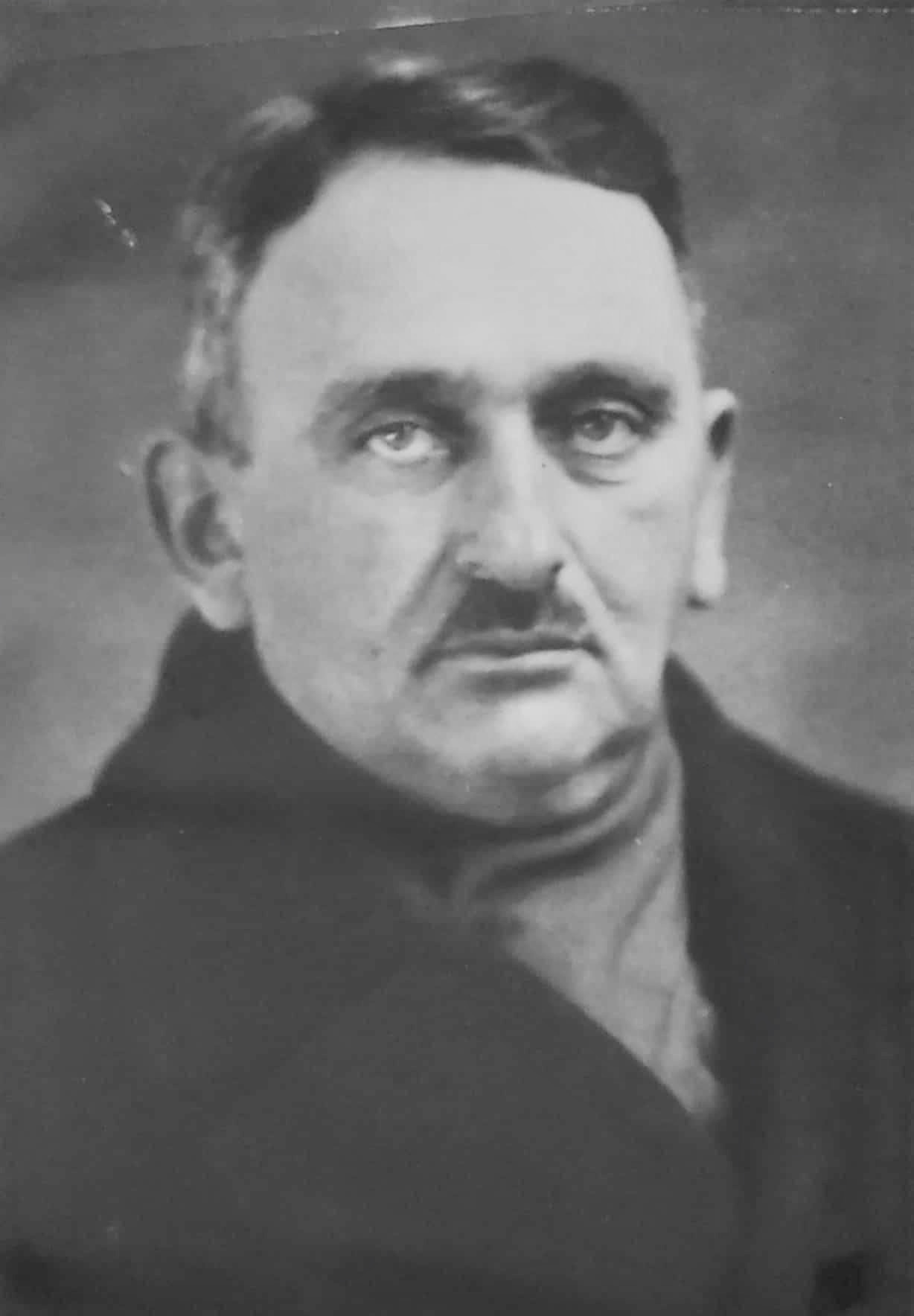

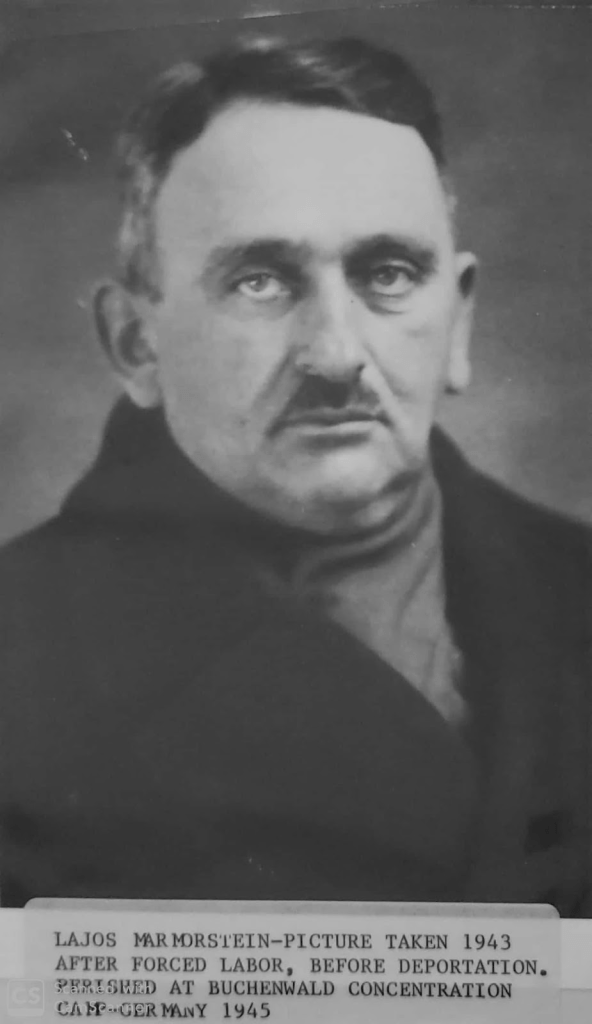

One photo stood out, though. It’s a man’s face that I’ve never seen before. He looks nothing like the Eastern European Jew of my imagination. He isn’t skinny or bookish, bearded or unkempt, pale or bespectacled. He doesn’t look softened from a life behind a desk or chubby from too many meals at the neighborhood deli. No, he looks weathered and worn, intimidating and tough. He looks like he has a hell of a story.

His eyes are dark; his look, defiant. He’s wearing a heavy black overcoat. I imagine him pulling the high collar up to protect him from a winter wind or to obscure his face from prying eyes. I can see him, late at night, smoking on some North Sea dock or walking the cobbles of some Central European city. He appears haunted but also rock solid. He looks straight into the camera lens, his gaze both weary from a lifetime of battles but also ready for whatever would come next.

The caption under the photo reads: “Lajos Marmorstein — picture taken 1943, after forced labor, before deportation. Perished at Buchenwald Concentration Camp, Germany 1945.”

On the one hand, the mystery is solved in a single caption. No sooner do I learn his name then I find out how the story ends. On the other hand, there has to be so much more. I will spend the following months following leads and making connections until the story behind the man in the picture came into focus.

* * *

The first connection I could make, though, went completely against the impression I got from the photo. My father had an Uncle Louis. Could this be him?

When the Marmorsteins immigrated, they anglicized their names: Morics, for example, became Max; my grandfather, my namesake, Jakab, became Jack. Nine Hungarian names became nine English names. Did Lajos become Louis?

The Uncle Louis I had heard about from my father was nothing like the man I saw in this photo . My father had never met Louis and knew very little about him. But in Louis’s case, the story was simple. You didn’t have to meet him to know it. In fact, one thing defined him to the exclusion of all else. Like most of his brothers and sisters, Louis left Transylvania for America. Records at Ellis Island show he arrived on September 2nd, 1922. He’s in a family portrait photographed in Cleveland a few years later. He had reached the safety and security that America offered.

Yet after a few years of living with seven of his siblings and both his parents in Cleveland, he somehow decided he would rather be back in Transylvania. The circumstances are lost to history, but the decision loomed large in family lore, and not in a good way. Lajos had bet that his future would be brighter back in Europe. Of all the bets a Jew in Ohio could possibly make in the late 1920s, this was the very worst. At the moment when hundreds of thousands of European Jews were clamoring to come to America, he decided to buck the trend. It was a bad decision on a world epochal scale.

Of course, it’s completely unfair to judge him for this, but judge him the family did. It didn’t matter that no one could have possibly predicted the coming catastrophe. Based only on this one decision, he had a reputation as the family schlemiel, the fool who bungles the one thing everyone else gets right, the loser who snatches defeat from the jaws of victory.

Could this be the man in the photo? Yes, of course. It is definitely that man. But the more I learn about him, the more I come to a very different conclusion about him. If Louis was unlucky, it wasn’t because he failed to foresee what everyone else also failed to foresee. And if he faced more adversity than his brothers and sisters, he also fought harder than any of them, too. Far from being the family schlemiel, Lajos might be the toughest of all the Marmorstein’s, a cunning fighter from his early life to his final days.

Hungary, 1869-1945

Lajos’ life hadn’t begun badly. In fact, he was born in what would later be called the Golden Age of Hungarian Jewry. During the period following Hungary’s 1869 Nationality Laws, Jews enjoyed a remarkable period of enfranchisement and prosperity. In fact, late-nineteenth century Hungary was one of the best places in Europe to be a Jew. The Jewish population enjoyed widespread legal and economic enfranchisement, and Jews responded enthusiastically, embracing their Hungarian national identities, taking up the language and culture, participating in economic and civic life, and inspiring waves of Jewish immigration into Hungary. Seventy-five percent of Hungarian Jewry spoke Hungarian as their mother tongue, and Jews punched above their weight in political influence in a country, where voting was linked with property ownership and education. In Budapest, for example, Jews represented about twenty percent of the population but forty percent of the voters.

Following the Nationality Laws, Jewish poet József Kiss exclaimed, “Finally, O Jew, your day is dawning!” Kiss, the son of poor orthodox parents and one of Hungary’s most popular poets of his time, announced that “Now you, too, have a fatherland!” In 1895, things seemed to get even better: Hungary became the only European country to officially recognize Judaism as a state religion. Historian István Deák would write that “no other country in Europe had been as hospitable to Jewish immigration and assimilation, and no other country had won more enthusiastic support from its Jews than the Hungarian Kingdom.” Raphael Patai wrote that “the twenty-five years between the 1895 Law of Reception granting equality to the Jewish religion and the Numerus Clausus Law of 1920 were the only period in the millennial history of the Hungarian Jews when legally no distinction whatsoever existed between the Jewish and non-Jewish population of the country.” [both quoted in Tim Cole’s “Hungary, the Holocaust, and Hungarians: Remembering Whose History”].

It’s not that this was all done out of goodness and idealism; there was a cynical side. The series of laws which granted Hungarian citizenship to Jews and other ethnic minorities were intended to boost the numbers of Hungarian citizens of the Dual Monarchy and gain Hungary additional influence in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The result, though, was incontrovertible: Jews enjoyed more rights in Hungary than in most any other country on earth.

This was the Hungary where Izsak and Esther Marmorstein married and had their children. Lajos, the second of twelve, was said to have been the most academically gifted and his parents sent him to study at yeshiva. But not long after the start of World War I, Lajos enlisted in the Hungarian Army and fought first in Russia and later in Italy.

Lajos Marmorstein, center, in uniform

During the war, assimilated Jews fought for Hungary in disproportionate numbers (estimates put the number of Jewish soldiers fighting in Austro-Hungarian armies at 300,000-350,000). Almost one in five army officers were Jewish, and over ten thousand Jews lost their lives in the war. Lajos was a corporal in the Army, earning commendations and medals for bravery in combat. He was severely wounded in the famous Battle of Piave River. His service and commendations were significant enough to be included in a book commemorating Transylvania’s decorated veterans of

World War I. It’s a beautiful volume, bound in blue fabric, embossed in gold, featuring the photos and service records of Transylvania’s war heroes.

When the war ended, Lajos was still recovering from his wounds. For Hungary, things were even worse. While the Treaty of Versailles is generally regarded as settling the end of World War I, the fate of Hungary wasn’t determined for another two years, when the Treaty of Trianon dealt Hungary the greatest loss of territory and population of any warring power. Hungary lost its seaports and the majority of its waterways and natural resources, including forests, coal, salt, and silver. Hungary also lost its ethnic diversity: Hungary’s Romanians, Slovaks, Croatians, Ruthenians and Slovenians were now citizens of other countries. More importantly, all incentives for Hungary’s multi-ethnic tolerance were gone. Post-Trianon Magyars represented 90 percent of the population, and the anger about Trianon easily fed a regressive nationalism that continues to this day.

What was happening in Hungary, however, wasn’t an issue for the Marmorsteins, though. They were among the many populations that found themselves living in a new country. Transylvania, which had always been populated by a mixture of Hungarian and Romanian speakers, was now part of Romania. This presented problems of its own, especially for the region’s Jews:

After the treaty of Trianon and the Romanian annexation of Transylvania in 1920, Transylvanian Jewry found itself in a double minority status within the newly created Greater Romania. The Romanian majority identified them as belonging to the Hungarian ethnic group because their mother tongue and cultural background was Hungarian, while within the Hungarian-speaking community they constituted a minority group because they were of the Israelite faith…. For them, the ‘golden era’ of the monarchy was over. (Zoltán Tibori Szabó, “The Holocaust in Transylvania,” in The Holocaust in Transylvania (2016), p. 148)

Finding themselves a double-minority in a new country, most of the Marmorstein siblings and parents would immigrate to America within five years. Lajos was a decorated military veteran of a country he now longer lived in, and in 1922, he left for America, the fourth Marmorstein to arrive at Ellis Island.

The family story is that Lajos struggled to learn English and was the most frustrated with low-paying, menial labor. Lajos’ later life would show that he was not easily daunted, nor did he shrink from a challenge, but America wasn’t for him, after four years, he returned to Középlak.

At first, it seemed like he had made the right choice. Not long after returning, there are newspaper reports of Lajos establishing himself in the region’s lumber industry. It was a particularly Jewish industry, as Jews had historically been forbidden from owning land for agriculture but permitted to own forests for harvesting for lumber. In some districts of Hungary, a business census showed that 90 percent of lumber mill owners were Jewish. [quoted in Faludi’s In the Darkroom].

Lajos also married and started a family. His wife, Ibolya Geist, was a dentist and seven years his junior. Together, they settled in Váralmás, a few miles from Középlak. They had two sons, Erwin in 1928 and then Elmer in 1930. Throughout the 1930s, the family thrived, living in a large house with servants, managing the lumber business and investing in other commercial enterprises in nearby Kolozsvár, and assimilating into the bourgeois society of the day. There are pictures of Ibolya at the tennis club and records of Lajos’ purchase of dry goods stores and making donations to Jewish charities.

Lajos, Ibolya, and their sons, Erwin and Elmer, in the mid-1930s, looking every bit the prosperous, assimilated family

For a while, events in nearby Germany and Austria seemed far away, but when Hitler turned his attention east, the Hungarians agreed to ally themselves with Germany and installed a government subservient to German wishes. In exchange, they received much of Transylvania.

The hardships Hungarian Jews experienced in Romania meant that they were initially optimistic when Hungarian troops returned to the region in September, 1940. Their optimism, however, was short lived, though. The new Hungarian government passed a series of anti-Semitic laws starting in 1940 and Jewish men began to be conscripted into the Kisegítő munkaszolgálat, the Hungarian system of forced labor, soon after.

Lajos may still have held out hope. Most of the anti-Semitic laws offered exceptions for veterans of World War I, and many veterans were the last to believe they would be betrayed by the country they had bravely served. But regardless, Lajos wasn’t exempted from Forced Labor. There’s no record about where he was sent. Some laborers were subject to the grim menial labor in mines, quarries, road construction, while others were sent to the Eastern Front, where they served, unarmed and unprotected, the Hungarian Army as it marched into the Soviet Union with Axis Forces.

The Lajos in the picture I found, decorated World War I soldier and former resident of Cleveland, Ohio, had just returned from Forced Labor, but having survived and finding his way home to be reunited with his family, he wasn’t content to lay low and stay out of trouble. In 1944, under growing pressure from Germany, the Hungarian government began to aggressively enforce the anti-Jewish laws that had been on the books since 1940. Even as Germany was in the midst of a catastrophic military collapse in the East and faced an imminent allied invasion in the West, the Nazis redoubled their efforts to make Hungary judenfrei. Lajos was still technically exempt from the worst of it, but his time in forced labor would have taught him what his exemption was worth.

So, when they came for the land of the region’s Jews, Lajos faced a choice. Reunited with his wife and young sons, he could have laid low. In fact, his foreman, a Romanian whose family were loyal employees of the Marmorstein businesses and household, offered to hide Lajos and his wife and children deep in the remote mountains, where no one could find them. But Lajos was tough, not the sort to give up his home and property without a fight. So when they came to take his 500 hectares, he refused to comply with the order. Even with the odds so obviously stacked against him, Lajos Marmorstein filed suit in court in Kolozsvár to fight for his legal rights.

The story of the court case was reported in the press, with two newspapers publishing articles about the defiant Jew fighting the anti-Semitic laws. On the 8th of March, 1944, Keleti Ujság reported that:

“A Jewish forest owner has been convicted of defamation. Under the law on the expropriation of Jewish property, the 500-acre forest of Lajos Marmorstein, a Jewish landowner living at 2 Gyulai Pál Street in Cluj-Napoca, on the border of Váralmás and Középlak, was also expropriated. Lajos Marmorstein challenged the expropriation decision in a lawsuit. He challenged before various public authorities that the State had the right to appropriate his forest land, which was his exclusive property. Criminal proceedings were brought against the disgruntled former forest owner for the defamation committed. Lajos Marmorstein was sentenced to three months’ imprisonment and three years’ disqualification. [fix]”

Rágalmazás miatt elítéltek egy zsidó erdőtulajdonost. A zsidó birtokok kisajátításáról rendelkező törvény alapján Marmorstein Lajos kolozsvári, Gyulai Pál-utca 2. szám alatt lakó zsidó földbirtokos Váralmás és Középlak határában fekvő 500 holdnyi erdejét is kisajátították. Marmor- steifl Lajos perrel támadta meg a kisajá tító határozatot. Ennek során különböző közhatóságok előtt is kétségbevonta, hogy az államnak joga lett volna erdőbirtoka ki sajátításához, amely kizárólagos tulajdon jogát képezte. Az elkövetett rágalomért bünvadi eljárás indult az elégedetlendkedö egykori erdőtulajdonos ellen. A kolozsvári — Személygépkocsinak ütközött egy tel törvényszék büntető hármastanácsa, Szabó jes sebességgel robogó motorkerékpár. Sú András dr. elnöklésével, háromhavi foghá zat és háromévi jogvesztést szabott kl Marmorstein Lajosra.

And on the same day, Ellenzek reported:

“KOLOZSVÁR, March 8 Lajos Marmorstein, a Jewish gentleman living at 2 Gyulai Pál Street, who was engaged in logging and woodcutting during the years of the Romanian occupation, acquired a 500-acre forest estate in the Váralmas–középlaki border. Under the provisions of the Jewish law, the state claimed Marmorstein’s forest. Mármorstein challenged the decision of the Állem court on appeal, but in his appeal he also used insulting terms. The Criminal Chamber of the Cluj Court sentenced the former timber merchant to 3 months’ imprisonment for defamation. The accused was acquitted, the prosecutor appealed for sulyosbitas. [fix??]”

KOLOZSVÁR, március 8. Marmorstein Lajos Gyitai Pál-utca 2. szám alatt lakó zsidó ezyén, aki a román megszállás éveiben fakitermeléssel és fakoresk désssel foglalkozott, az évek folyamán a Váralmas–középlaki határban 500 holdas erdöbirtokra tett szert. A zsidótörvény rendelkezései alapján az állam igénybevett Marmorstein erdejét. Mármorstein az állemi határozatot fellebbezéssel támadta meg, de fellebbezéséban sértő kitételeket is használt. A kolozsvári törvényszék büntető hármastanácsa rágalmazásért 3 hónapi fogházra ítélte a volt fakereskedöt. A vádlott felmentesert, az ügyész sulyosbitasért fellebbezett.

Lajos, the “Jewish Forest-Owner,” went down fighting. From decades of studying the Holocaust, I’m familiar with the Jews’ many forms of resistance: from taking up arms against the Nazis to hiding or escaping; from living under assumed identities to all manner of subterfuge–forging documents, smuggling food and medicine, bribing officials. They did whatever it took to survive another day. But I’ve never heard of anyone choosing the path that Lajos did: even after years of forced labor, he didn’t run and hide, or try to evade the law through dissimulation or fraud, or weather the storm by keeping a low profile. No, in March 1944, Lajos Marmorstein went straight to the courthouse in the capital city of the region and filed suit against the signature anti-Semitic policies of the Nazi-puppet government.

Of course he never stood a chance. He not only lost his property but was held in contempt of court and sentenced to three months in prison. Alas, his prison sentence would have been preferable to the fate that awaited all the region’s Jews just a month later. Starting in April, 1944, Jewish property was confiscated en masse, and Police departments were instructed to take immediate action to prevent Jews from hiding valuables, selling them, or giving them to others for safe keeping. Jews were excluded from professional organizations and lost employment in the public and private sectors. They were forbidden to own telephones, radios, firearms, or printing presses. Beginning on April 5th, they were required Jews to wear Star of David badges.

Later in April, ghettos were established in Transylvanian cities. All Jews were forced to leave their homes and crowd into these ghettos, where they lived in unsanitary conditions, malnourished and mistreated, under constant fear and frequent torture and abuse. Starting in May, Jews began to be deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau. By June, at the same time that Allied forces were landing on the beaches of Normandy, cattle cars carried nearly 12,000 Hungarian Jews to Auschwitz each day. The entire process, from expropriating Jewish property to the deportation to death camps, took less than eight weeks. Randolph Braham, a historian of the Hungarian holocaust, writes that it was “the most concentrated and brutal ghettoization and deportation process of the Nazi’s Final Solution program.” [quote in In the Darkroom]. All told, out of a total population of 165,000, estimates are that 125,000-130,000 Jews from Northern Transylvania perished during the Holocaust.

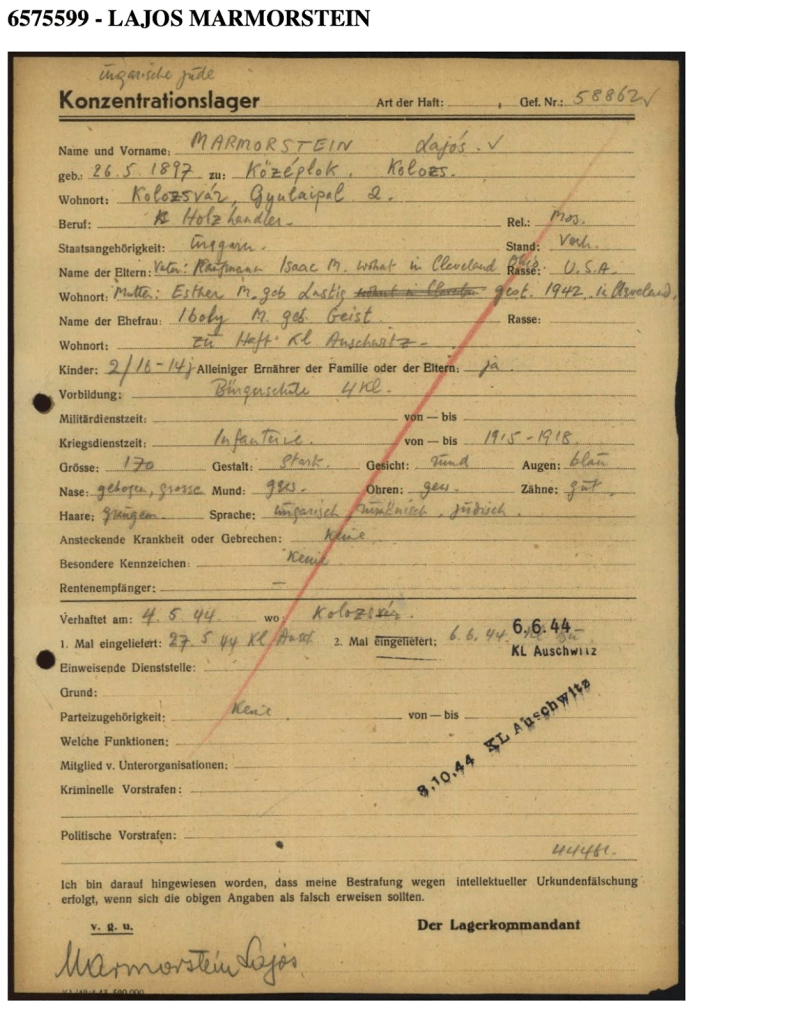

From this point onward, most of what is known about the fates of various Marmorstein’s comes from the records that the Germans kept of their Final Solution. Lajos was deported from Kolozsvár and arrived at Auschwitz-Birkenau on May 4th, 1944. His wife Ibolya’s arrival was processed the day after him, on May 5th, 1944. She was immediately sent to the gas chambers. Their elder son Erwin arrived at Auschwitz-Birkenau twenty days after his mother. Erwin’s younger brother Elmer, who was thirteen at the time, gave his age as fourteen when he arrived at Auschwitz two days later. He must have heard that those under fourteen were typically sent straight to the gas chambers, while those fourteen and over were sent to the labor camp.

[paragraph naming other cousins, aunts and uncles who were also deported to Auschwitz that month]

Lajos’s Auschwitz entry paperwork records many of the same things a typical application for a driver’s license or a passport might. There’s his physical description: height, weight, hair and eye color (as well as some anti-Semitic categories like “nose”). There’s information about his home address, the date he was deported, and his “category”—in his case, Hungarian Jew. There are blanks for level of education (“Bürgerschule 4Kl””), profession (“lumber jack”), and military service (“infantry). The most striking entry, though, is under the category of “Parents.” Here, the name of Izsak and Esther Marmorstein are duly recorded, as are their birth years. There’s one final blank, for their place of residence, their Wohnort. The answer stuns me. “Cleveland, Ohio, U.S.A.” It’s the truth, but somehow seeing it on this form leaves me speechless. It makes explicit the connection I’ve known from the start. It draws a straight line from a Nazi death camp to the immigrant family in Cleveland that I grew up with. For Lajos, entering a German camp system he would never leave, it must have been a dark moment to think that he had been there, with them. Now, though, he was at Auschwitz.

I wondered what Nazi bureaucrat had asked Lajos about his parents’ Wohnort and received this unexpected answer? Had Lajos spelled “C-L-E-V-E-L-A-N-D” and “O-H-I-O” for his captor, who would almost certainly have been unfamiliar with the place name? Would Lajos have recalled his life in Cleveland and wondered about al life that had taken him from the trenches of World War I, to immigrant life in the US, and back to Transylvania could possibly have ended here, spelling the name of the midwestern city where he once lived to a clerk at a Nazi death camp.

Lajos would survive at least another ten months, moved between a variety of Nazi camps, until his death, just weeks before liberation. His children, as well as a half dozen of his nieces and nephews, would survive Nazi death camps and make lives for themselves in Israel or America. And seventy-five years later, his great grandson would send me the digital archive that his granddaughter had collected, and I would find his picture, and rewrite the story of Uncle Louis for a new generation of Marmorstein’s.

* * *

So, there I was, in the spring and summer of 2020, discovering the story behind the picture. What I learned sometimes hit a little too close to home. A pandemic, the Trump administration, the murder of George Floyd and the Black Lives Matter demonstrations. Mass upheaval and political instability didn’t seem limited to Europe seventy-five years earlier.

If there was a lesson to Lajos’s life—and the lives of millions like him—it’s how catastrophe could sneak up on you. Lajos couldn’t know when it was time to stop fighting and start running. He refused to take up his foreman’s offer to hide him and his family. He fought, and why wouldn’t he? It was his property, his business, his money, his home. It was land that even seventy-five years later, would be known as “of Marmorstein.” Who had the right to take them away from him? How could he have known what he was up against?

How would we know when it was time to empty the bank accounts, gather up the passports, leave life here behind, and flee to safety? What even did that mean? Could we flee to some isolated mountain compound, living off-the-grid? Or to someplace like Israel, where, reduced to tribal warfare, my tribe would be the strongest? Or maybe just northern Norway, where my contracting work would have taken me, if we had been able to leave our house.

How would I know when it was time to leave? When shortages meant that you rationed out the basics? When the ICU’s were full, the morgues, overflowing, and the hospital ran out of ventilators? When the bridges in and out of the city had been closed? In the spring and summer of 2020, all those things happened around me, and by the time I realized it, it was too late to flee.

Of course, political stability was restored, the curve was flattened, and vaccines were discovered in record time. The supply chain held, as did the economy, and our democracy, more or less. Were our fears exaggerated? Did I overreact? Or had we gotten lucky? Catastrophe hadn’t struck, but I didn’t exactly feel safer.