In the Spring of 2020, during the first months of Covid times, Yom HaShoah, the Jewish Holocaust memorial day, began at sundown on April 20th. April 20th, 2020 was also the 75th anniversary of the Allied bombing of the German town of Memmingen. For most, this coincidence was nothing but random trivia, but for me, it meant that the day commemorated the dead on both sides of my family, Jewish and German alike.

I’ve always known that my father had cousins who survived the camps. We would see some of them at family reunions and on trips to Florida. It wasn’t something we talked about, though. I doubt anyone knew the actual number of Marmorstein survivors spread around the world, and I’m sure that no one compiled the complete list of those Marmorsteins murdered in the Holocaust. Even now, after five years of research, I’m far from definite answers.

I first learned about the bombardment of Memmingen from my mother on a 1987 trip to visit her family there. It would have been impossible to explain the relationships between the relatives we were visiting without referring to those killed that day. I can’t say I paid much attention; I was eighteen and the intricacies of the family tree went right over my head. My German family had always felt quite distant, even as my mother had several first cousins there.

Twenty years before our 1987 trip (and two years before my birth), my mother had converted to Judaism before she married my father, and together they raised me in a fully Jewish household (Hebrew school, Kosher kitchen, Bar Mitzvah, etc). These German relatives were part of my mom’s childhood, before she became Jewish, but they hadn’t been part of my childhood until we visited them. They made an impression during our visit, though–they were warm and hospitable hosts and we had a wonderful week with them.

After that trip, I didn’t give much thought to my German family until recent years, when I cleaned out my parents’ attic and found boxes of their letters and documents. These shed new light on their lives and offer a vivid picture of the family, before and after the war. There is one letter that particularly stands out as the emotional crescendo of a thirty year correspondence. It is the first that my grandfather received from his sister Clär after the war, typed on a worn typewriter ribbon, leaving barely legible text on a piece of paper so light that it flutters on the table in front of me every time I exhale.

The letter informs my grandfather of the wartime death toll: since he last heard from his family, my grandfather lost his mother, his two brothers-in-law, one of his sisters, two nephews, and a niece. In an otherwise brief and matter-of-fact accounting of the deaths–including the deaths of two nephews killed in combat in Ukraine–one paragraph opens like an open wound on the page. It’s the paragraph that describes the April 20th bombing raid that killed their sister and her family:

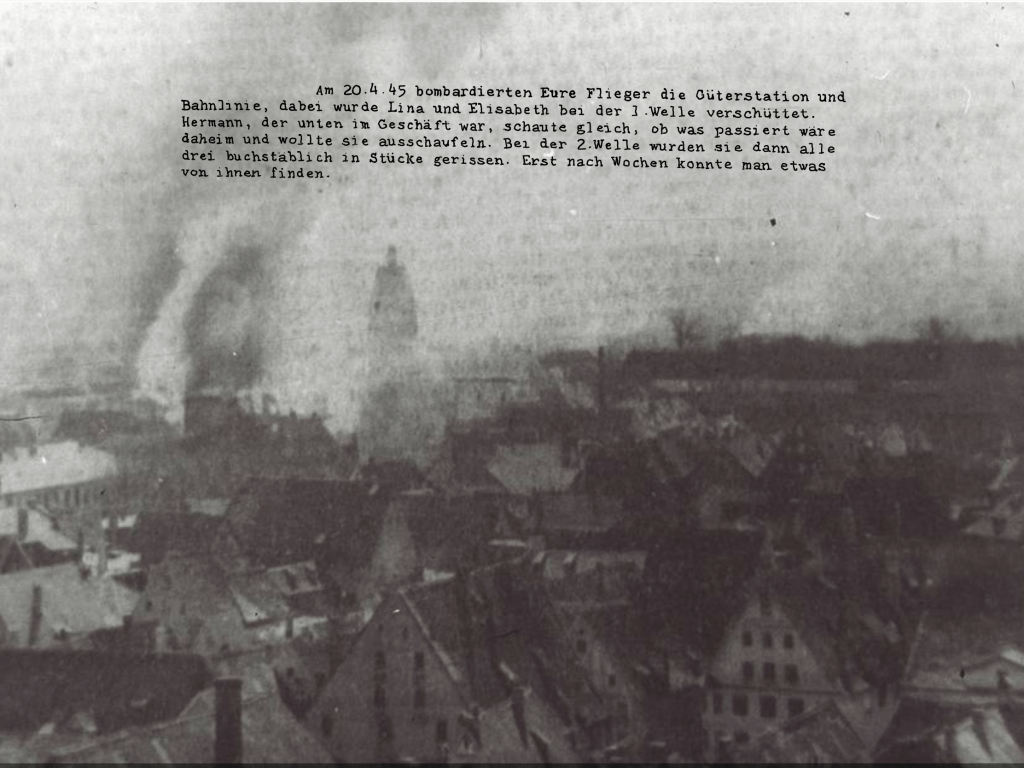

“We had had a few attacks on Memmingen and we always got through well. On April 20, 1945, your airmen bombed the freight station and railway line, and Lina and Elisabeth were buried in the 1st wave. Hermann, who was down in the shop, immediately checked to see what had happened at home and wanted to dig them out. In the 2nd wave, all three of them were literally torn to pieces. It was weeks before anything of them was found.”

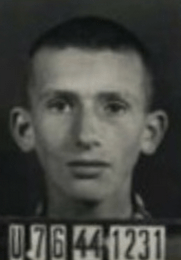

The Jewish Marmorsteins–those whose property was stolen, who were rounded up in ghettos, deported to Auschwitz, gassed or enslaved in labor camps, and death marched in the war’s closing weeks–left no letters describing their agony. There is no doubt, however, of their path through history’s most lethal hatred: the Nazi’s maniacal documentation left a paper trail of the suffering and agony. The Häftlings-Personal-Karten, the prisoner ID cards, of my father’s uncles, aunts, and cousins are available, online, from the Arolsen Archives. There’s only one photo but it’s enough: my father’s sixteen year old cousin, Erwin, staring into the lens of his some Nazi camera, his cheeks sunken, his eyes a combination of the lost boy he must have been and the defiant survivor he was becoming.

When I stare into Erwin’s eyes and think about Tante Clär’s letter, her suffering engenders not sympathy but scorn, especially when she ends her letter with the melodramatic plaint: “This is the lost war. All our men are criminals. One can only envy the dead.” She’s right about the war, of course, and about her men. But I imagine that Erwin saw a lot of the dead and never envied any of them.

Yet is it really a contest? Tante Clär voiced her suspicion of Nazism in letters from the early 1930s, and she went to great lengths to keep her son out of the Hitler Youth. In later years, her kindness would make an enormous difference in my mother’s life. When she wrote that letter to her brother in January 1946, she was hungry and cold; her sister, brother-in-law, and young niece had all been killed, in the bombing of a civilian neighborhood, just a few weeks before the end of the war.

Does your heart harden when you imagine their suffering? Or does it harden only when you compare their suffering to those packed in cattle cars and gassed at Auschwitz or tortured at labor camps? Is it really a contest between sufferings? Must we conflate the call for historical justice with our capacity for empathy in the face of human suffering? On April 20th, on Yom HaShoah, are we judges or mourners?

**

In the mid-1990s, a high school kid in Florida videoed an interview with Erwin’s brother, my father’s cousin Elmer, about his experience in the camps. While the high school kid tries to lead Elmer to a very Hollywood version of the Holocaust, Elmer resists, offering a version both more boring and more bleak. In Elmer’s telling, the experience wasn’t a struggle between sadistic madmen and heroic resisters; rather, it was a dehumanizing slog through the daily banalities of hell. Asked whether the guards were “especially cruel, like in Schindler’s List?” Elmer answers, “Some were, some weren’t…. Actually the guards were half young SS men, and some of the old Wehrmacht, which was the old army. You could tell a difference. One enjoyed being cruel, the other one was kind of sorry, you know, they’d shrug their shoulders.”

Fifty years before, Elmer had caught the eye of some Wehrmacht soldier who had shrugged his shoulders, as if to say how the hell did we end up here, as if they had both found themselves in a madness over which they themselves had no control. Of course there can be no moral equivalence between concentration camp inmate and guard, and there is no comparison between their suffering. It’s easy to feel rage at that guard–how dare he deny his complicity in the cruelty and injustice that surrounds him? What can it possibly mean that he’s “kind of sorry”?

Yet even Elmer hasn’t lost his capacity to empathize with him. Who hasn’t felt their helplessness at the cruelty and injustice that surround us? Climate change? War in Ukraine? Refugees at the border? What can I do? What side am I on, really? Could my own urge to judge the guard reflect my own shameful awareness that under the right circumstances, I could be on either side of the equation: prisoner or guard, victim or perpetrator?

The confluence of Yom HaShoah and the anniversary of the bombing of Memmingen brought these impulses inside me to the negotiating table. Could imagining both sides–Elmer’s and his guard’s; my Marmorstein family and my German family–help me understand both parts of myself, rather than embracing one and denying the other? Some would say that if I mourn Nazi and Jew alike, it will lead to some abyss of moral relativism, but perhaps the opposite is true. Perhaps it’s only by mourning both that I learn to offer more than a shrug of my shoulders in response to the suffering of the other.