Max Marmorstein’s story was truly larger than life. Max never cut a heroic figure, but he also seemed to make an impression: one society columnist called him “a hail fellow-well-met,” and another described him as “truly distinctive” and a “squatty fellow.” He could kindly be called round, with high-waisted pants, a stiff smile, and a narrow trimmed mustache that went out of fashion with Hitler. Max was a wit and a character, never shying from the spotlight and never conforming to expectations. In other words, he had a personality to match his fortune, and he accumulated wealth and power on a scale that still inspires awe three generations later.

Max hosted the Truman and Eisenhower families. Max discovered Hollywood songstresses. Max’s horses won races at Churchill Downs. Max brought an Israeli second cousin to Cleveland for cancer treatment and bought apartments for other Israeli relatives. Max stood up to US Senators, hung out with the Mayor of New York, and owned hotels from Detroit to Key West. Max went back and forth to Europe to escort family members to the US, went to Israel to make sure his family was well taken care of there, and vacationed in Havana. His estate near Cleveland is now the suburb’s palatial city hall.

Max, my father, and Vincent R. Impellitteri, former mayor of New York City, at Max’s Casa Marina Hotel

If you were to ask Max how he rose to such heights, he’d tell you he began by building houses, then invested in office buildings and theaters, and finally found that hotels were his specialty. If you were to ask the Senate Committee on Organized Crime in Interstate Commerce, they might have different ideas. The family, though, never countenanced any blemishes on Max’s reputation, and in his inimitable style, Max would brand these suspicions “not only fantastically false but utterly irresponsible.”

Max’s story began many decades before he started arguing with Senators in 1950. He was the eldest Marmorstein and the first to immigrate in 1913. Little is known about his early years in America, but there are a few indications that he sometimes adjusted facts in his favor and that he occasionally ran into obstacles along the way. In the 1920 census record, he’s listed as a boarder with ten other people in a house on Woodland Avenue, but when he arrived at Ellis Island in 1920 for the second time (having returned to Romania to accompany Jakab (Jack) and Adolf (Eddie) to the US) he listed his address as the prestigious Williamson Building, home of Cleveland’s Federal Reserve and about as far as from an immigrant boarding house as possible.

There’s also a modified 1917 Registration card: under the heading, “Race (specify which)” someone had first written “Jewish”, but then “Jewish” is scratched out and replaced with “Caucasian.” The cross-out job is half-hearted–”Jewish” can still be read easily, and “Caucasian” is added with a much lighter pen or perhaps a pencil. In other words, there’s little effort to truly deceive, yet there’s a nudge along the path from the immigrant-boarder-Jewish identity and towards fitting in in America.

Document with “Jewish” crossed out and replaced by “Caucasion”

He didn’t always succeed in accelerating his American-ness; a registration card indicated that he was denied naturalization in 1921, though it gave no reason why. By the 1930 census, though, he was a naturalized citizen, but even that census contains an untruth: it back-dated his arrival in the US two years, to 1911. It’s impossible to know whether this was an innocent mistake, but if it wasn’t, it would fit with his habit of adjusting the facts a bit to make himself a little more American at every opportunity.

Document showing that Max’s naturalization was denied in 1921

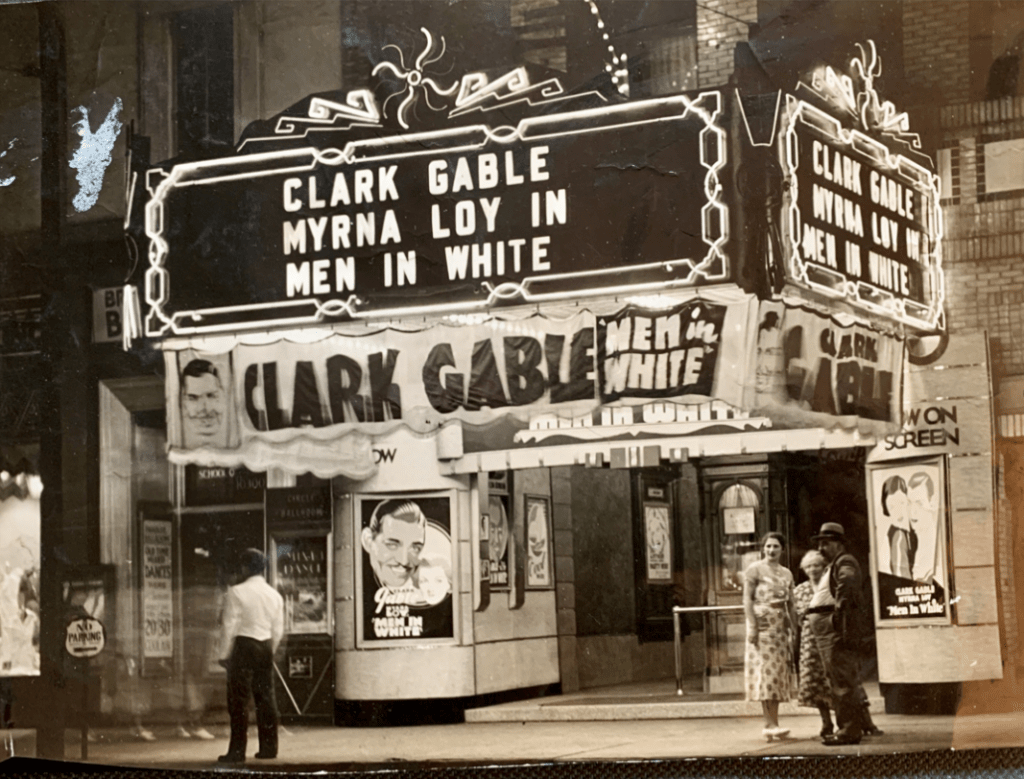

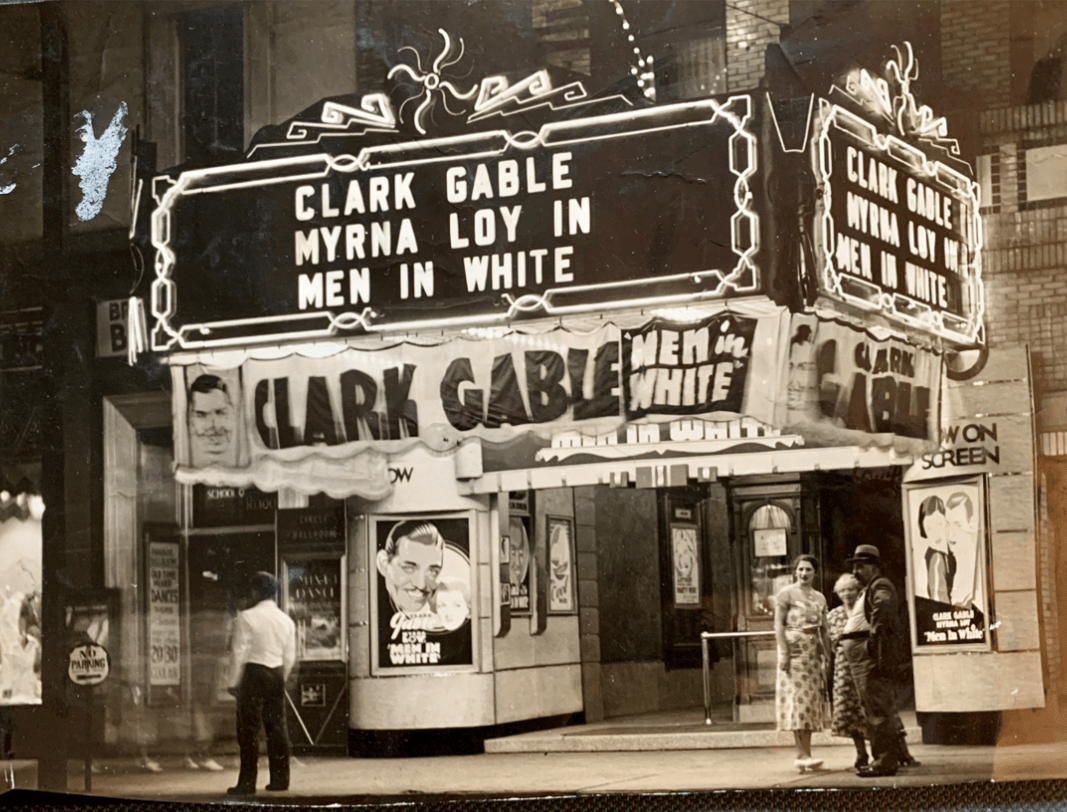

Regardless, by the mid-20s, Max was already making an impression in the region’s real estate. In 1927, he owned the Circle Theatre in Cleveland and opened Hotel Grant in Detroit. Some of these buildings he built or purchased, but in many cases, he “represented,” or was a “consultant” to, the owners of hotels like the Wofford, the Raleigh, The Blackstone, and the Soledad.

Max, far right, with my grandmother and great-grandmother, Sadie Marmorstein and Rebecca Finamen, at the Circle Theater in 1934

In the early 1940s, Max made news for his racehorses, with articles about his Black Swan winning the forty-second running of the Bashford Manor Stakes at Churchill Downs (Cincinnati Inquirer, 5/1/43, p. 13) and others winning races in New Jersey and Delaware. Later, when he was questioned by Senators, Max would say that the “only gambling I ever do is on horses,” a quip that was repeated in newspapers across the country.

Press coverage of Max from that era was quite positive: in addition to his winning ways at the racetrack, he’s mentioned for various philanthropic efforts, and there’s a 1948 article about bringing an Israeli relative and holocaust survivor to the US for cancer treatment. He also helped other Marmorstein holocaust survivors make their way to the US or Israel and paid to get them settled in their new homes.

In 1949 and 1950, Max got really busy. In the Fall of 1949, he made an unsecured loan of $25,000 for “a hotel, or something like that, out west” to Thomas J. (T.J.) McGinty, a loan that would come under Senate scrutiny two years later and that put Max squarely at the origins of Las Vegas. A year later, on October 1, 1950, newspapers reported Max’s purchase of the Casa Marina hotel in Key West from Florence M. Barnes of Chicago. The Casa Marina would be Max’s pride and joy. According to a local columnist, “Max…husbands his hotel like a mother,” and according to another, he approached the Casa Marina’s renovation with the mind of a “builder and a psychologist.” The family would also come to know the Casa Marina well. Max would host legendary family gatherings there, and family members are still regaling the generations that followed with stories of the grandeur of the place.

But the Casa Marina wasn’t Max’s only focus. Several months before, an investigator named Daniel P. Sullivan had named Max in testimony before the Committee of the United States Senate to Investigate Interstate Criminal Activities, and on November 6, 1950, Max sent a letter to the committee demanding its retraction. Sullivan is quoted saying that Max’s “telephones were taken out of that office in 1943 because they were connected with gambling operations” (p. 157), and Max is apoplectic. In typical Max style, he approaches the committee with a politeness bordering on obsequious, but follows with a fierce defense and thinly veiled counter-accusations:

As one citizen who has been seriously harmed by the completely unfounded testimony relating to me given by Mr. Daniel P. Sullivan, I...urgently request that your committee take immediate steps to correct the transcript...To lay a foundation for the fairness of my request, I shall summarize briefly the testimony of Mr. Sullivan…, how it has been interpreted by our local newspapers, how utterly false they are...and the irreparable economic, social and personal harm that I have sustained.

He goes on to show myriad errors in Sullivan’s testimony, from dates not lining up to botched chronologies to impossible causal connections, and concludes that “the testimony was not only fantastically false but utterly irresponsible and reckless because the most superficial investigation would have disclosed its falsity.” After hundreds of words over three dense pages, his civility returns and he concludes with this:

I trust with this explanation you will be able to correct your records and the transcript of the testimony to accord with these facts. Please be assured that I shall be glad to supply you with any further information concerning my or my activities which you may care to have.

Thanking you in advance for your interest, I am

Respectfully yours,

Max Marmorstein

It should be noted that Sullivan wasn’t just any old investigator. According to his New York Times obituary, he “helped track down John Dillinger and later had a long career fighting organized crime in Miami.” He also earns a footnote in history simply for the lists of names he compiled in his testimony. Alongside Max, there are the famous one, like Alfred “Big Al” Polizzi and Meyer Lansky, and others whose nicknames themselves deserve to be remembered: Alfred “Poagy” Toriello, Jimmy Blue Eyes, Abner “Longie” Zwillman, Joseph Jasper Aiello “alias Fats”, William G. Bischoff “alias Lefty Clark,” and “Mushy” Wexler.

Thomas J. (T.J.) McGinty was not mentioned by Sullivan, but he became the focus of Senators’ questioning three months later. In January, 1951, Max was sworn in to testify in person before the “Special Committee to Investigate Organized Crime in Interstate Commerce” in Cleveland, Ohio. The hearings were presided over by Senator Estes Kefauver, whose role would be so prominent that the entire effort took his name, coming to be known as to be known as the “Kefauver committee” or “Kefauver hearings.” Kefauver would leverage his prominence all the way to his candidacy for Vice President on Adlai Stevenson’s losing 1956 presidential ticket.

As far as I can tell, Max wasn’t subpoenaed to testify before the committee; rather, he approached them to make his case to remove Sullivan’s damaging testimony from the record. Nonetheless, Max ends up on the hot seat, and his reparté with the Senators is priceless, with Max confidently correcting, denying, evading and charming the Senators in turn. It’s worth quoting at some length:

Mr. Halley. You made a loan to Tom McGinty?

Mr. Marmorstein. Yes; I did.

Mr. Halley. Under what circumstances?

Mr. Marmorstein. Oh, he asked me if I could loan him some money; he wanted to go in some enterprise, and I said I would be glad to.

Mr. Halley. When was this?

Mr. Marmorstein. Oh, I think it was in the fall of 1949.

Mr. Halley. Did he tell you what enterprise he wanted to go into?

Mr. Marmorstein. Well, he told me he was figuring on building a hotel, or something, out West.

Mr. Halley. Did he tell you what kind of hotel?

Mr. Marmorstein. He told me it was a hotel.

Mr. Halley. Did he tell you where?

Mr. Marmorstein. I believe he did. He told me it was in Las Vegas.

….

Mr. Halley. To your knowledge, has McGinty ever been in any hotel operations before?

Mr. Marmorstein. No.

Mr. Halley. Now, when he came to you and asked you for money, did he ask you for a specific sum ?

Mr. Marmorstein. I believe he asked me if I could give him $25,000 or $50,000. I told him that I couldn’t spare $50,000, but I could loan him $25,000.

Mr. Halley. And what did you give him?

Mr. Marmorstein. I believe I gave him a check for it.

…

Mr. Halley. And at that time, did you know McGinty’s background and occupation?

Mr. Marmorstein. Oh, yes. I have known him for 25 years.

Mr. Halley. Did you know he was in the gambling business?

Mr Marmorstein. I didn’t know he was in the gambling business. I know [sic] him years ago, when he was in the fight-promoting business, and bicycle races, and so on. I had read in the newspapers that he had some gambling establishment he was connected with; but, outside of that, I don’t know what.

Mr. Halley. What collateral did you get from your $25,000?

Mr. Marmorstein. I got a note from him.

Mr. Halley. Well, a note isn’t collateral, of course.

Mr. Marmorstein. No; no collateral, just a note.

Mr. Halley. You just loaned him $25,000 on his note?

Mr. Marmorstein. On his note; that is right.

Mr. Halley. And without any knowledge of the transaction he was going into.

Mr. Marmorstein. Without any knowledge; that is right.

…

Mr. Marmorstein. If I had the money, I would loan Mr. McGinty $500,000 if I had the money.

Mr. Halley. Have you been in the practice of lending large sums of money to people without collateral?

Mr. Marmorstein. Yes. If I know a man, I don’t ask for collateral.

….

Mr. Marmorstein. All 1 want to say is this, that my files are all upstairs, whatever they are in connection with the Wofford deal, with the Raleigh deal, with any other deals that are involved and as I said in my letter to you on November 6, if at any other time you care to have me, I will be glad to appear, and I thank you for the privilege of appearing here. I would like to get back to Key West. I have got a nice hotel there. I will leave you a folder of it. [Laughter.]

If it is good enough for our President, it ought to be good enough for us.

The Chairman. Now we have somewhere we can stay in Chicago, and when we go down to Key West

Mr. Halley. I would vouch for the Casa Marina. It is one of the most beautiful buildings in the country.

The Chairman. You own all of that ?

Mr. Marmorstein. I own all of that, Senator, and I have no

Partners.

The Chairman. I was interested in knowing this: ‘How much interest did you charge Mr. McGinty?’.

Mr. Marmorstein. I charged him interest, Senator.

The Chairman. Big interest?

Mr. Marmorstein. No, no. But I did charge him interest.

…

The Chairman. All right, then. Fine. We will take this over and

study it, and it will be made an exhibit. (The paper identified was thereupon received in evidence as exhibit No. 73, and was returned to witness after analysis by the committee.)

Mr. Marmorstein. Senator, can I go back to Key West now ? Or

shall I still — —

The Chairman. Have you got another one of those folders ?

Mr. Marmorstein. Yes; I have. [Laughter.] I brought this up to give you a folder.

Mr. Halley. When I saw it, it was under the Navy management.

Mr. Marmorstein. Well, it is much prettier now, sir. Since then, Mrs. Barnes remodeled.

**

Having made his case–and invited the committee to the Casa Marina–Max might have hoped to stay out of the news for a while, but no such luck. In March, he’s mentioned in a major investigation on the front page of the Philadelphia Inquirer, “N.Y. Police Pocket 25 Million yearly In Underworld Graft, Senators Told; O’Dwyer Crony Indicted for Perjury.”

I have no information about how the investigations resolved themselves or of any implications for Max. By the mid-50s, though, the news is better. A front page article in the Key West Citizen covers the return to the Casa Marina of Betty Madigan, a singer who credited Max with giving her her big break. She was returning the favor by headlining his New Year’s Eve celebration. Two years later, Max is back in the papers for serving President Eisenhower’s son his first piece of Key Lime Pie. Around this time, too, the Cleveland estate that was once his home opened as the City Hall of Wickliffe, Ohio. My father took us there once, reminiscing that he and his cousin could bring their baseball mitts and play catch down one of the spacious corridors.

Betty Madigan: An headshot autographed to my grandparents and an article about her and Max

Max didn’t live a long life. He died in 1961, at the age of 65. Late in life, he had married his longtime companion Florence. The Casa Marina is now a Waldorf Astoria resort, and where his enormous wealth went is as mysterious as how he got it in the first place. The family gossip is that he was in trouble with the IRS at the end of his life and died just before much of his wealth was taken in back taxes and penalties. I haven’t seen evidence of this, but there isn’t any other good explanation for the disappearance of his fortune. There’s some trace of a philanthropic foundation that bore Florence’s name, but it seems inactive for decades.

The closest the family ever came to acknowledging anything fishy about Max’s rise came when a young cousin read a newspaper headline and innocently asked Pearl, the family matriarch, if Max was in the mafia. Pearl denied the charge with a vehemence that kept the cousin from mentioning it again for decades. Pearl’s fierce defense came with the admission, though, that Max had once “run some errands for some men.”

Regardless, Max’s trajectory likely wasn’t that of a criminal mastermind but of an immigrant’s hustle, good timing, and ambition. In a New Yorker article called “The Crooked Ladder,” Malcolm Gladwell expands on the sociologist James O’Kane’s description of the “crooked ladder” of social mobility for ethnic immigrants in early 20th century America. Reading O’Kane’s study of organized crime families, Gladwell concludes that “crime was the means by which a group of immigrants could transcend their humble origins…The point of the crooked-ladder argument…was that criminal activity, under those circumstances, was not rebellion; it wasn’t a rejection of legitimate society. It was an attempt to join it.”

Hi – I came across Max Marmerstein when I was reading about the Raleigh Hotel in South Beach history and learned he owned 50% of it in 1940’s! I lived in one of the Florida Keys for some time and had no idea he owned Casa Marina too… incredible. Thank you for posting this

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s amazing, Hugo. Thanks for the information about the Raleigh Hotel. If you find anything more interesting about Max, let me know. He’s quite a legend in my family.

LikeLike