Like many children of boomers, my sister and I faced the formidable challenge of cleaning and selling our parents’ suburban house. My parents hoarding had been unchecked for decades and had taken over most of the rooms in their four bedroom colonial. Given the complexities of my mother’s medical situation, one entire bedroom functioned as a medical supply store room. My sister’s and my rooms hadn’t been seriously altered since we last lived in them in the early 1990s, except that additional boxes and containers had been stacked along walls, serving as overflow for other rooms. Other rooms were full of spare parts, extra furniture, old clothes, and purchases that were often never even unpacked. My father had a basement and workshop full of tools, ranging from the practical to things like containers of leftover battery acid and a drawer full of toilet paper rolls. My mother had a collector’s tendencies and there were hundreds of Beanie Babies, as well as dental hygiene tools dating back to the 60s.

The task of cleaning all this alternately filled me with fascination and rage. There was archeology to be done; mysteries to solve; connections to be made; and curiosities to satisfy. I could access it all, without limits, without judgment, without sneaking behind backs or dissimulating motives. And the plunder was all ours. Nothing was off limits: the proscribed treasures; the toys saved for grandchildren then deemed too fragile for them to play with; the pasts perfectly preserved, never to see the light of day… It was all ours now.

Yet the scope of the task was unimaginable, and the habits that left this burden to us were infuriating. We worked demanding jobs; my sister had her young son; we lived several hours from my parents’ house, and here we were, spending weekend after weekend, month after month, and thousands of dollars on dumpster rental and trash hauling alone, let alone the normal expenses of moving. No matter how hard I tried to have compassion for my parents’ circumstance, I could help feeling like they had done this to us. They had been unable to get rid of anything; worse still, they had seemed to conclude that this was a victimless crime, a harmless foible. How had they been so blind to the mess they were leaving us to clean up?

But they had borne so much. Their lives and their situation had gotten harder with each passing year–my mother became increasingly impaired; my father sacrificed so much to care for her. This wasn’t part of the plan. The piles in their house had just grown bigger, the chores, more insurmountable. Bedrooms became supply closets and storage spaces. Finally the whole upstairs is really just another attic, and the state of disrepair became permanent. My dad even put a sign on the bathroom door, “Under Renovation, 2008-Jan 1st, 3142”.

**

There was something even bigger going on, too. Struggling to find your way through the mess, movement constrained by piles falling in on all sides, it all seemed symbolic of constrained lives, of defenses against fears that had ended up being barriers to living. The traces of lives unlived were everywhere: letters from the Peace Corps asking my mother when she wanted to leave for her assignment; the information my parents had once read about immigrating to Israel; itineraries for European trips that they couldn’t take because my father couldn’t get off work; and boxes of videocassettes full of Oprah’s meaningful conversations, all of which my mother watched while suffering through our family’s testy exchanges and persistent silences. Everywhere I looked, I saw the ways my parents came to be ever more helpless against their anxieties.

It was infuriating, heartbreaking, and also liberating. It reminded me of the desperation I had felt throughout my childhood, and I had to remind myself that it couldn’t suck me back there. There were little things that were hard to throw away, even as keeping them made no sense whatsoever: my mother had kept all my baby teeth, as well as bars of soap imprinted with the retro TWA logo, and her wedding shoes. Some things could be treasured by another generation (Star Wars pillowcases, Snoopy towels); other things just brought back such powerful memories (the veterinary records of our childhood dog and cat, and my father’s favorite cap; my mother’s kitchen apron). Most sentimental of all might have been finding my mother’s coffee cake deep in the freezer–it was her special recipe, one she was particularly proud of. As we thawed it and ate the final pieces, my sister and I knew that it would be the last thing our mother would ever feed us.

Finally, after filling four construction-site size dumpsters and innumerable trips to Goodwill, most of their life is in the county dump or at thrift shops, and what remains is with me in Philadelphia. There are things I still regret throwing away, but I took cell phone pictures of so much and can scroll through my photo library when I want to return, either to the awful clutter or to the bittersweet memories. These pictures bring back the texture of the red wagon I rode in, the wooden step stool that I used to reach the bathroom sink, and even the tile pattern we had on our bathroom floor. I learned that I remembered things by how they felt in my hand–everything from the zipper pull of my childhood coat to the buttons on my Star Wars digital watch brought back as many memories when they were between my fingers as when they were before my eyes. They’re gone now–no need to burden the next generation. The cell phone pictures will have to do.

What I kept, though, was every possible connection beyond my parents to the previous generations of their families. I had their father’s names; I wanted to see what my parents had hidden away about who they had been. What follows is what I discovered. Not everything was in the attic the whole time, but much was, and much else was unlocked by the attic’s content. My parents had stacked their defenses–and decades of junk–against memories they couldn’t bear. The memories were in the grave, but the artifacts could finally be excavated. The thought could be energizing, but it was always tempered by my feelings of melancholy about their lives–both how they had lived their lives, and how they had lost them. It all seemed so sad.

The Attic

I can’t remember my earliest memory of the attic. The ladder to the attic swung down from a trap door in the ceiling in the upstairs hallway outside my bedroom. I remember the trap door cracked on summer nights to let the attic fan draw a pleasant breeze through the house. On the rare occasions the door was completely open and the ladder was unfolded, I recall being fascinated by the whole mechanism: the textures of the unfinished wood, knotty and splintery; the sandpaper traction strips adhered to each step; the black metal hinges and springs that guided the ladder as it unfolded and refolded, squeaking and creaking like a creaky old body stretching after months in the same position.

I’m sure I wanted to climb the stairs as soon as I saw them, but it was years before I was permitted to scale even half the ladder; and years after that before I could climb high enough to see the unfinished attic, lit by a single bare bulb and chock full of boxes to the edges, where the bare floorboards stopped and only open insulation extended to the eaves. Later, I would watch my father when he was in the attic, and I began to get some sense of where things were: when pesach approached, he brought down the pesach dishes there; when we needed the sleeping bags for slumber parties, they were to the left; or when the seasons changed and we brought down plastic garbage bags full of our off-season clothes, they were right at the top of the ladder.

Beyond the usual, I knew there were two things in the attic with a special place in the family hierarchy of importance. The first was the slide projector, and the boxes of slides from my parents’ travel to Europe and Israel the year before I was born. These were frequently talked about and rarely seen. The task of organizing them was on my parents’ to-do list for as long as I can remember. Their 1940s slide projector–a hand-me-down from my mother’s parents–had none of the convenience of modern projectors, and loading and unloading the slide trays was slow and cumbersome. My parents seemed to want to organize them before showing their children, which meant that we very rarely saw them at all, perhaps a half dozen times in my entire life.

When the slide projector was set up and the images projected on our white living room wall, it seemed like a wonder–both the colorful images, four feet across on our wall, and the images of my parents having adventures half a world away. On balance, though, most of the stories remain untold, most of the slides, unseen. Now that I have them all at my fingertips, I can only guess the stories behind them. The other mysterious treasure in the attic was my fathers collection of Volume I, Number I’s, the first issues of magazines that I guess some people collect (though I’d never heard of such a thing and even my parents’ explanation left me confused for years). I had always thought that collections were intended to be shared, and collectors eager to show off their collections. But like so many other things deemed “valuable” in my household, this designation rendered them untouchable, hidden from view and from the damage that their handling would cause. My father bragged about having the Volume 1, Number 1 of Life magazine, but he never once showed it to us. It was only when I finally found the collection myself that I realized the other reason that the collection remained hidden in the attic.

It wasn’t until I was twelve or so that I got the idea to go explore the attic by myself. I was excited by what I might find, but what I actually found exceeded the dreams of any pubescent boy. I was fascinated by my father’s collection for the most innocent of reasons: I wanted my father to have something special, to be extraordinary in this way. I treated the uncovering of the collection with appropriate care. I handled the first issue of Life magazine as the treasure that it was, but almost immediately, I was introduced to many other topics that spawned new magazines in the 1970s: various versions of feminism (Ms, Playgirl, Viva (“The Magazine for Women,” ft. Joyce Carol Oates and Norman Mailer), Women’s Sports (ft. “How to Win” by Billie Jean King); general lifestyle trends: two magazines about CB radio, “Gamblers [sic] World, Marriage and Divorce (ft. “Marriage a la Mode” by Philip Roth), Rush “the magazine of high entertainment,” Chips “For the Winners of the World,” and The Runner. I can appreciate the music magazines more now than when I was young in the early 1980s: Teen Beat, Hard Rock, and especially Punk Rock, which offered cool spreads on Iggy Pop, Blondie, the Ramones, and the Sex Pistols. Then there were uncategorized titles, like Hot and Black, and Nitzotz, the radical newspaper of the Radical Zionist Alliance, with a giant red Star of David on the cover. Most of these were lost on my adolescent mind, but the other titles, deeper in the box, were like buried treasure. There, I found all manner of dirty magazines, from classy girlie magazines to the raunchiest porn my young mind had ever seen. Whatever other secrets were held in other boxes in the attic, my adolescent self never got past the Volume One, Number One collection.

**

Decades later, when I next found myself in the attic, it was to throw out the detritus of fifty years. The 70s era sleeping bags and off-season clothes, the empty boxes that my parents kept for purchases above a certain value, as if they might need them to repack the TV or VCR, miscellaneous household goods (broken fans, wobbly end tables, kitchen chairs that would never be repaired, etc.): all destined for the dumpster. Most heart wrenching were the old toys, but they had no place in our current life, and I was determined not to store them for a few more decades and pass the burden on to my own children. I had to brace myself against the tears whenever I would load another trash bag full of old stuffed animals and board games; old dolls and action figures; my prized slot car racing track and erector sets. The smell of mildew and rot was so bad that I wore a mask whenever I was in the attic, and it was easier to throw things away when a single whiff of them would make my eyes itch and my nose run.

I grew quite accustomed to the utterly crazy things that my parents held on to: things like boxes of cardboard toilet paper rolls, empty bottles that were once filled with cleaning supplies, clothes that no one had worn since the 1980s, electric blankets with bare wires sticking out of them. So when I came across a crumbling paper bag full of moldy smelling dowels, wrapped in newspaper that had been eaten away by bugs, I was ready to throw them in the trash bag, but something made me hesitate. It wouldn’t be the first pile of scrap lumber that I had found up there, squirreled away for fifty years for the occasion when it might be needed. Could these be anything different? The amount of garbage in the attic was overwhelming, and I made decisions quickly and sometimes carelessly. At times I despaired at finding anything of interest, but I never quite lost hope and pulled the dowels out of the trash bag and grabbed one to examine it more closely.

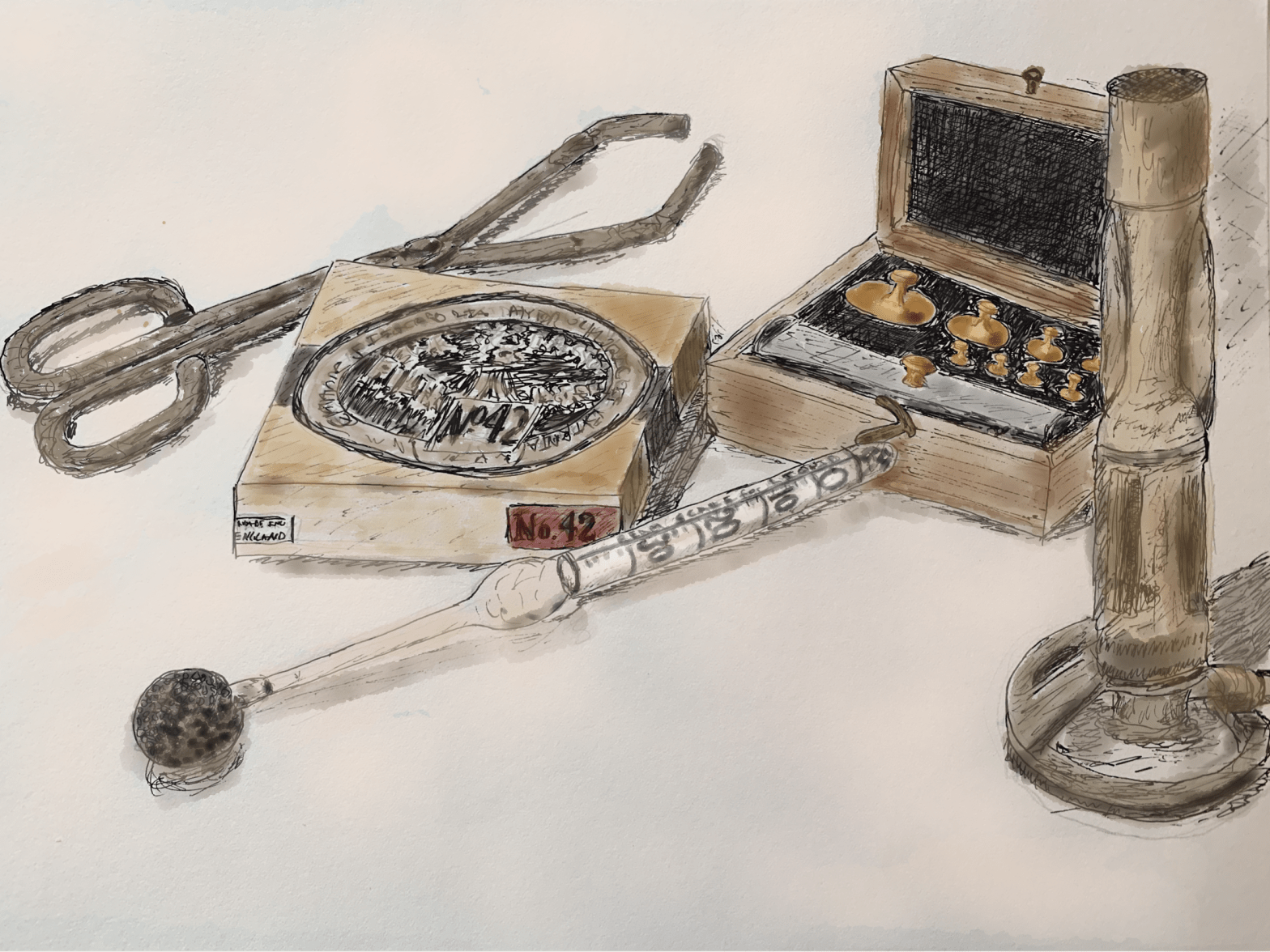

The first thing that struck me was that the dowel was light, as if it was balsa wood. Then I noticed that there was some sort of seam halfway down the dowel. I began to tug at either end of the dowel, and the dowel revealed itself to be a wooden tube that separated into two parts. When I pulled it open, very old cotton packing fell out and revealed a glass tube. I brought the whole bag carefully downstairs where I could examine them in the light. Each tube contained a different piece of my grandfather’s delicate chemistry equipment, various instruments to measure the composition, density, pH, or specific gravity of a fluid. The glass was artfully blown in different shapes, with delicate calligraphy marking the units of measure. And there weren’t just these tubes, but also bunsen burners and weights and balances; test tubes, filters and beakers. All of it was perfectly preserved from when my grandfather had used it to refine the science of leather tanning, nearly a century before.

Seeing them jarred obscure memories of my mother talking about her father’s chemistry equipment. It had been forbidden when we were children, but I had two strong recollections from being told about it: the first was my mother’s awe at how special and precious this equipment was; and the second was my mother’s fear that anything might happen to it. This latter returned to me when I cringed at how close I’d been to tossing it in the dumpster, but it also connected me to my mother’s fear of her father. His precious, delicate equipment needed to be protected at all costs, even if that meant it spent fifty years in a bag in the attic. Possession and safety were of primary importance; actually enjoying the possession was never really a possibility if it meant risking its safety.

My mother’s fear was often palpable, and often heartbreaking. Even when there was so much to fear–cancer, chemo, radiation, death–it had always seemed like her fear came from a long time ago. Indeed, she was fearless in pursuing the most aggressive cancer treatments, yet plagued by worries that her family heirlooms weren’t safe in her hands. Ultimately, perhaps the fear wasn’t so much for the objects themselves, but for the retribution she had experienced for angering her father. It’s a testament to the power of her fear that made me remember that distant moment in my childhood when my mother had shown me her father’s paddle, and wonder if I would find it, too, in the attic.

Ultimately, along with the chemistry equipment, I liberated the slides and the boxes of family letters and artifacts that have revealed my family’s stories to me. I unearthed all the stories that my parents had buried during their lifetimes. I found the only remaining traces of the men I was named after. I could investigate all this freely, without fear of my parents’ judgment or defensiveness, but that meant that I would be investigating alone. I would never get to tell my parents what I discovered. My questions for them would remain forever unanswered, my assumptions and hypotheses about them, forever unconfirmed.

Thanks so much for sharing this poignant chapter! I read it once, then returned to read it again after poring over successive chapters of your family history. Despite the pain of plowing through your parents’ stuff, your choice of descriptive words made me smile. Many of us can identify with parts of this journey with our parents.

LikeLike